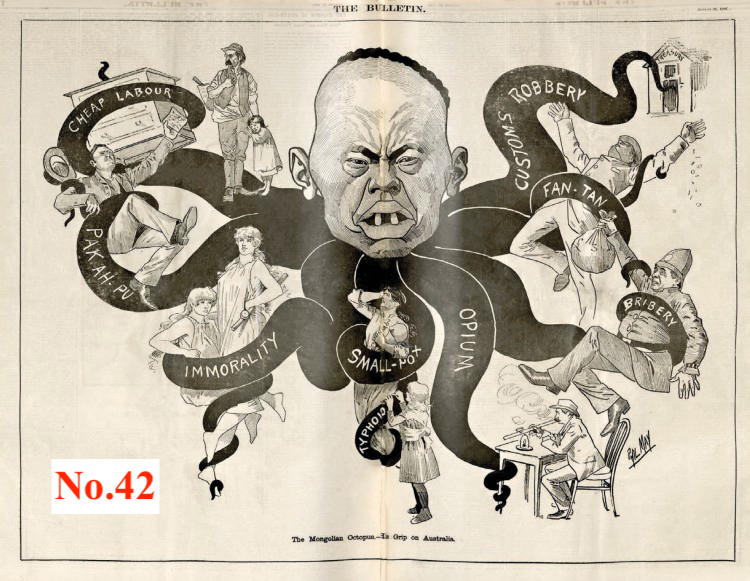

“The Mongolian Octopus” is perhaps one of the most readily identifiable racist cartoons in the world – even today often imitated when anyone wishes to illustrate a long reaching and seemingly insidious threat. First published in The Bulletin in the same year – 1886 – that this popular nationalist magazine changed its masthead from “Australia for Australians” to “Australia for the White Man”, this one cartoon seems to sum up all that the “white man” thought and feared about the presence of Chinese people in “their” land. Certainly this summation was the intention of the editor who employed the newly arrived English illustrator Phil May to create this poster for an issue devoted to denouncing the presence of Chinese in the Australian colonies.

An evocative and powerful image such as “The Mongolian Octopus” can be the engine of its own success, with constant use and reproduction of the cartoon – particularly in the age of the Internet – creating an impression of its influence that becomes self-fulfilling. In other words, a cartoon designed for a white nationalist magazine, albeit a popular one, striving to impose its view of the world on an Australian community comes to be held up as representative of that community. Success indeed. But is this authentic?

While cartoon’s such as this that appeared in The Bulletin and other newspapers and magazines are a convenient and effective means of illustrating what some people undoubtedly thought all of the time, can they be used to prove that this is what all of the people thought even some of the time? Obviously not. But the simple overuse of the octopus cartoon has perhaps given the impression that this was all there was to the white Australia debate even within the pages of The Bulletin itself. One danger in such a lack of nuance is that when racism and discrimination is painted in only such stark terms it is harder to recognise its continued existence in its present day (also nuanced/sly) forms.

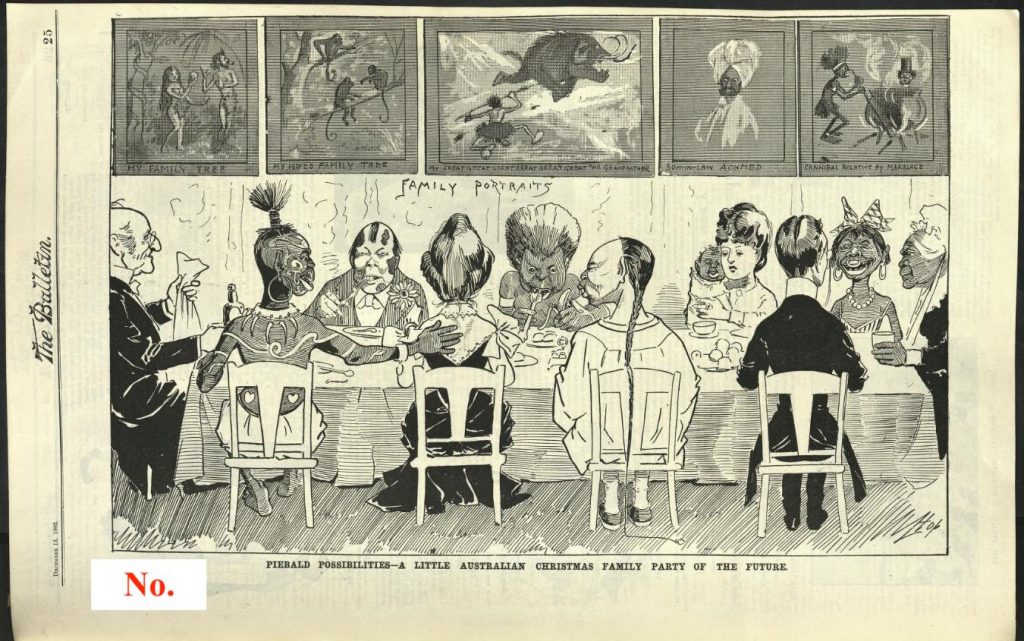

Nevertheless “The Mongolian Octopus” remains an interesting and instructive object of Chinese Australian history as long as it is remembered that it was created as a tool for a particular viewpoint and continues to be used as a tool even if nowadays for different purposes. Another cartoon that can be used to illustrate just how much things have changed is “Piebald Possibilities” which also appeared in The Bulletin, several years later in 1902. Here the intent was to illustrate a possible fear, only to inadvertently predict what many would recognise (absent the fashion sense) as a typical multicultural Christmas celebration in many Australian homes today.

Cartoons, as with all images including photographs, are not reliable sources of historical information unless placed in context. Images are too powerful and too easily reproduced until their very recognisability becomes part of their self reinforcing power to impose a particular perspective. How familiar is the image of the well-dressed man in spectacles (or are they sun-glasses) just arrived in Melbourne in 1866? Why does this clash so strongly with our dominant images of Chinese miners and market gardeners?

This is not because such images are inaccurate but merely because they have a tendency to self-replicate and push aside alternative images. Stereotypes, including stereotypical images, are not wrong because they don’t exist, they are wrong because they substitute for nuance, individuality and all that makes up historical reality. The ‘success’ of The Mongolian Octopus and the broader project that was the White Australia Policy is that it continues to make it difficult to see Chinese Australian history in its full scope. The cafe proprietors (see No. 11), doctors (No. 66), opera performers (No. 16), veterans (No. 43), Christian missionaries (No. 2), newspapermen (No. 86), temple custodians (No. 10), and home builders (No. 21), as well as the politically active (No. 44), the authors (No. 11 & No. 22) and unionists (No. 87) are made more difficult to see. Or if seen at all they are too often perceived as exotic “exceptions” to the norm, rather than as the fundamental elements of the norm they in fact are.