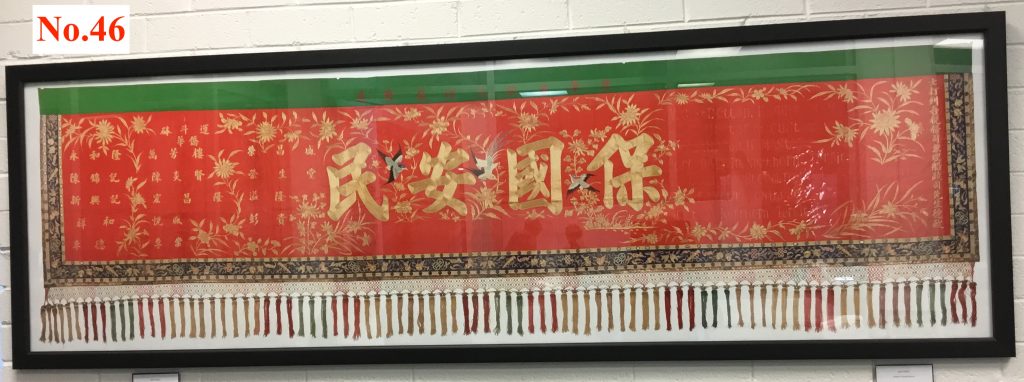

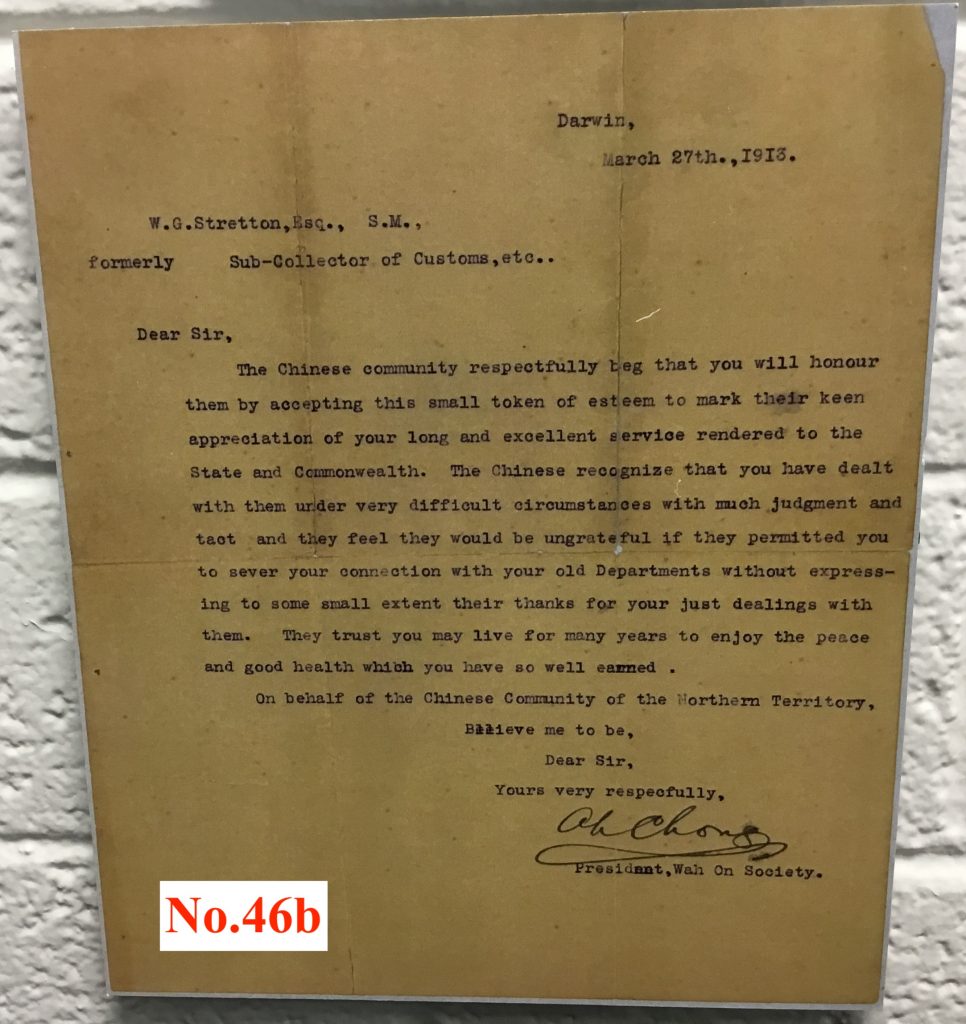

This handmade silk banner was presented in 1913 to William George Stretton, a retiring official of the Northern Territory administration. Like the gold medallion presented in 1869 to retired a gold commissioner (No.9), the Chinese community was expressing its gratitude to a government official who they felt had treated them well, or at least not unfairly. The banner reads ‘protect the country and the people’ (保國安民) and is now to be found in the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory. (Though the image here is in fact of a copy now hanging in the National Archives room, Darwin.)[1]

Such presentations were common in China, as they were also among non-Chinese Australians in the period, but they take on a special pathos when the vulnerability of the Chinese community to both official and community racism is taken into account. This is even more the case when it is noted that Stretton was retiring mainly from the Northern Territory administration of the South Australian government for which he had worked on and off for much of his life. Whatever the attitude of other members of this administration those of Chinese and more generally non-white heritage in the Northern Territory found themselves treated very differently by the Commonwealth Government administration which took over the Northern Territory in 1911.

By one of those all-too-common co-incidences for which history (unlike novels) is famous, this change of attitude is startingly marked by another banner of a sort. Cotton rather than silk, symbolic of the new Commonwealth and seemingly marking a high point in ‘White Australia’ ideology. This ‘banner’ was the flag used at the ceremony held in Darwin in 1911 just a year or two before Stretton was presented with his silk banner. The Australian flag found itself in dispute because it was thought to have been made by Chinese Australians. This was an extreme attitude that many, though by no means all, white Australians were also critical of.

Darwin and the Northern Territory found itself at the centre of these exchanges of hostility and gratitude over pieces of cloth, both cotton and silk, because unlike communities further south it had a substantial non-white population. Darwin, as did perhaps only Cairns in Queensland, had a majority Chinese population for a time. This was something White Australia policy faddists were determined to change and after 1911 a number of measures were taken to restrict the work opportunities of Chinese and other non-white people in Darwin and in the now Commonwealth controlled Northern Territory. These efforts even brought in the last Qing representative Consul-General Tong Ying Tung who pointed out that no distinction was being made between those who were “Foreign Subjects”, “Naturalised British Subjects” or “Australian born British Subjects” whether descended of foreign or naturalised parents. The faddists recognised no distinctions in their racist desire to achieve a white Australia and this no doubt meant that the work of people such as William George Stretton was all the more appreciated.

For more on the flag controversy and the efforts of the Qing Consul see: Ultra-White Australia Faddists and a Qing Consul

[1] For images of the original and more detail on this banner see, Kate Bagnall, “The Stretton Chinese banner”, Journal of Chinese Australia, Issue 1, May 2005.