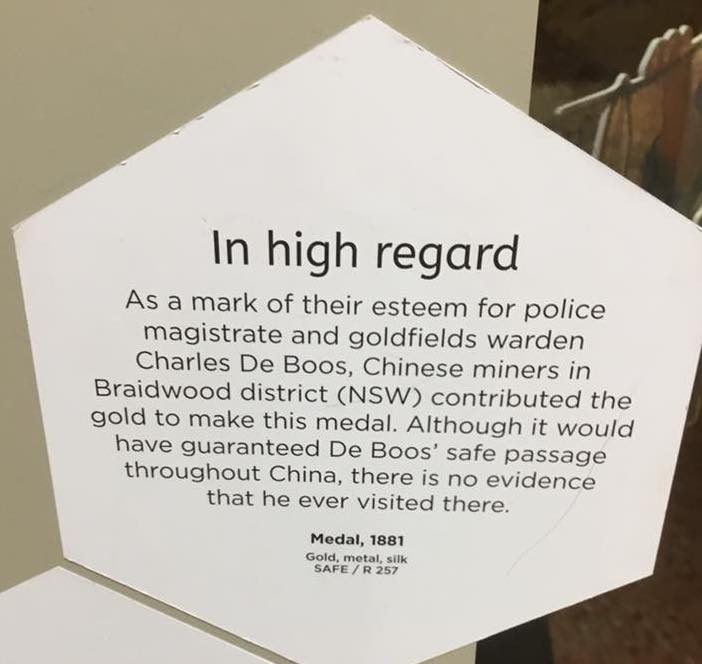

This gold medal, now in the State Library of NSW, was given to a local Braidwood Magistrate, Charles De Boos, – who also acted as Gold Fields Warden – on his retirement in 1881. It was given by the local Chinese community and is inscribed in both Chinese – poorly so the engraver was evidently not Chinese – and English. The giving of something of this nature to a retiring official who is considered to have done his job well would have been natural to the Chinese Australian community of Braidwood and was also very common among the wider community of 19thcentury Australia.

The medal and its subsequent treatment as an historical artifact tells us a number of interesting things. First and foremost it informs us that the relationship between the Chinese Australian community and this Braidwood official was an amicable one. While this is not the ‘Lambing Flat’ inspired stereotype, in fact, it was not an uncommon situation and was particularly so in former gold fields communities such as Bendigo in Victoria and Braidwood in NSW.[1]

However it is how the medal has been seen and treated once presented that gives us most information. The State Library of NSW catalogue quotes an unnamed newspaper clipping of the time:

In 1874 [De Boos] was appointed a police magistrate and mining warden…The Chinamen in the Braidwood district subscribed a piece of gold each, from which was designed and presented to him, a Chinese medal. Armed with this “passport” it would have been possible for him to have travelled all over China without molestation.

A similar account is to be found in other newspapers of the time.[2] What is interesting here is the immediate exoticising of the medal with the nonsensical idea that such a decoration could be used as a ‘passport’. Images of inscrutable Chinese ways are immediately called forth. But this was in 1900 on the cusp of the establishment of a White Australia. Yet remarkably in 2019 when the State Library of NSW displayed this medal it endorsed this passage.

The library’s catalogue also translates the medal’s inscription but in a fashion that is instructive of the lack of nuanced awareness of Chinese Australian history and heritage – or Chinese history and heritage for that matter. Thus we are given:

First line: Qing guan min le

[Since you are] such a “Qing guan” (honest and upright official) people are happy

Second line: Zai Buliehuo

In Braidwood

Third line: Tangren jingsong

Present to you by the Chinese with high respect

A more lucid translation (care of Ely Finch, translator of The Poison of Polygamy – see No. 11) would be:

Honour in an official is joy in his people,

Respectfully presented by the Chinese people of Braidwood. [3]

What is noteworthy about the State Library translation is that the transliteration is given only in Mandarin – a language not spoken by the 19thcentury arrivals from China in Australia. The community of Braidwood would have spoken either a variation of the Cantonese language and many also the separate See Yip (Siyi) language. That they did not use Mandarin is obvious in the rendering of ‘Braidwood’ phonetically as ‘Bu-lie-huo’. In Cantonese it would be the more accurate “Bo-lit-woot”.

The fault lies in part with English being limited to the use of the single word ‘Chinese’ to convey both people and language for a diverse culture and heritage. Chinese Australian history takes part in that history and heritage, and an awareness of dialect, language and regional differences is important because it was important to the people – such as those who presented De Boos with his medal – whose history it was.

[1] See Barry Mcgowan, Reconsidering race: The Chinese experience on the goldfields of southern New South Wales, Australian Historical Studies, October 2004, Vol.36 (124), p.312-331.

[2] For example, The Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, 3 Nov 1900, p.10.

[3] The (presumably European) engraver seems to have mixed up the order of the first two characters. Ely Finch feels it should probably have read “官清民樂” not “清官民樂”.