1911 marked an interesting year in the history of both the Northern Territory and China. For China it was to be the final year for the Qing Dynasty while in January the Northern Territory was formally transferred from South Australia to the Commonwealth.[1] While the fall of imperial rule was to be symbolised for China with a new flag, for the Northern Territory it seems an old flag proved more symbolic.[2] Attended by “whites, Asiatics, and aborigines” the new Australian flag intended to be raised over Darwin was protested against by what even the Sydney Morning Herald dubbed “ultra-white Australia faddists”. For the protestors the problem was that the flag to be used was considered unacceptable because it was made by local Chinese tradesmen, people who had been “naturalised since Port Darwin was established”, and despite the fact that many Chinese merchants had turned out in “national costume” for the flag raising ceremony. In its stead an “old and tattered flag” – one not known to be made by Chinese as one wag put it – was hoisted and the Northern Territory passed into the care of the Commonwealth of Australia.[3]

While the flag faddists were being lampooned (though not entirely without support), with wit and in one case poetry, the new administration quickly got down to the more serious business of making the Commonwealth safe for its white destiny.[4] In this case by, within a matter of weeks, the “closing of the avenues of employment” of non-white peoples or “Asiatics” as the term was, in “mining, fishing, coolie labor on the wharf and in gardens”. What the specific intention of those responsible for this was is unclear, but one result was an organised protest by 40 to 50 now unemployed “Chinese and Malays” demanding either “employment or rations”.[5] A well argued petition declared “it means great hardship and in many cases starvation”.[6]

Like laughter over the flag, this news too made its way down south, this time all the way to the last Qing Consul in Melbourne. Consul-General Tong Ying Tung[7] in an interesting letter to the Minister of the Department of External Affairs declared that the “officers of your Department are operating most harshly against Chinese residents in the Northern Territory”. Consul Tong referred to a number of instances of discrimination and hardship, and pointed out that no distinction was being made between those who were “Foreign Subjects”, “Naturalised British Subjects” or “Australian born British Subjects” whether descended of foreign or naturalised parents. Finally the Qing representative in Australia felt that it was “almost a work of supererogation” when he needed to point out that naturalised British subjects gave up their previous nationality in expectation of having “all the rights and privileges of British Subjects.”[8] Regarding those that were subjects of the Emperor, the Consul-General argued that, with Chinese numbers down and the Commonwealth in full control of its immigration, to treat these small numbers of “innocent persons” so harshly would seem “unnecessary and deplorable”. Not to mention the damage to the fishing industry he had already pointed out.[9]

The department’s reply was unhelpful, and it seems deliberately misleading, declaring that it didn’t know what was happening in the north regarding “Asiatics” and that “the question” of fishing regulations “has not been determined”.[10] The writer of this letter, Department Secretary Atlee Hunt had only the month before informed the Acting Administrator of the Northern Territory that for those claiming to be British subjects a “certificate from the Hong Kong Government” was required for a fishing licence.[11] In fact, a reply by this official implies he was acting on the basis of “an interview with the Hon. the Minister”. The result of which interview apparently was that those of Chinese birth were to be targeted, even though the difficultly of exempting “British subjects of Asiatic parentage”, i.e., born in Hong Kong, was also acknowledged. Despite Hunt’s note, Birth Certificates were deemed unreasonable to demand so it was left to the administrator to be “guided by the best evidence practically available”.[12] With what result we have some idea.

This Qing representative left Australia soon after this and his replacement shortly found himself representing a republic. In the meantime the Chinese people of the Northern Territory continued to protest their treatment including sending a deputation to meet with the new Minister of External Affairs, Josiah Thomas when he visited Darwin in May 1912. A note of this meeting clearly outlines the grievances they were suffering under:

- The 1903 Mining Act prohibited any “Asiatic Alien” from working on a “new goldfield” unless they had discovered it. In fact, all mining – wolfram, tin or otherwise were often proclaimed goldfields to prevent Chinese working on them. [And what was defined †o be “new” could be extended.]

- Under the 1910 Aboriginal Act no “Asiatic Alien” could employ an Aboriginal person, forcing a butcher out of business for lack of workers to look after his cattle for example.

- European labour to be used under tender conditions and so many who worked on the wharfs are now unemployed.

- The 1903 Commonwealth Naturalisation Act prevented an “Asiatic” from becoming naturalised and lack of naturalisation in turn prevented purchase of land.

- The “Chinese centres” of both Darwin and Pine Creek were declared “prohibited areas”, that is, Aboriginal people could not go there, and so much business was lost.[13]

While the Minister declared, “Chinese residents of the Territory must receive fair treatment”, he also said that the “White Australia” policy must not be violated.[14] Local reports, however, show some sympathy for Chinese people and also some doubt about the value of a “white Australia” approach:

“The members talk, however, more soberly of a white Australia. They see that the difficulties of population and of developing the tropics with white labour are tremendous and costly. Some also recognise the injustice of the treatment meted out to Chinese who were born here or have lived many years in the Territory. The Government policy is to close up every avenue of employment, and practically starve them out. Most of them are too poor to return to China. By proclaiming every mineral field a goldfield, whether wolfram or tin, the Government practically proclaims that the position is that many Chinese are a burden on those better off and will soon be a burden on the Government.” [15]

The contradictory nature of the issue was well summed up:

“White workers say that the tribute system should cease and Chinese labour should be prohibited. Employers say that the mines would he unworkable without Chinese, and that the whites at present available are quite unsatisfactory, owing chiefly to drink.” [16]

Perhaps even more telling was this account of the Parliamentary party of Minster Thomas as it toured the Northern Territory:

“The trip, which should have occupied 12 hours, took 24, owing to faulty pilotage. A Chinese boatman had to pilot, the [returning] party to the Daly mouth.” [17]

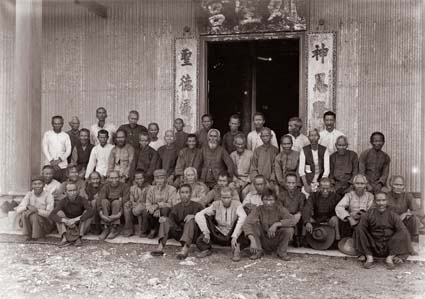

These efforts to discourage Chinese and other non-whites in the Northern Territory, coupled with their freedom post-Federation to move without a poll tax into other States resulted in just that increase in the “burden on the Government” predicted by the Observer writer in 1912. In a 1914-1915 effort to clean up the Darwin Chinatown on health grounds large numbers of elderly Chinese often living on government rations were discovered. Some 60 or more “old and debilitated men” were encouraged to return to China with free passage, a present of £3, and a promise from them never to return.[18]

[1] Northern Territory Times and Gazette, 6 January 1911, p.2 & The Sydney Morning Herald, Wednesday 4 January 1911, p.9.

[2] The new flag of the Chinese Republic flew in Port Darwin at the end of 1911, The Sydney Morning Herald, 23 November 1911, p.9.

[3] The Sydney Morning Herald, Wednesday 4 January 1911, p.9. Wag – The Register, 7 January 1911, p.14.

[4] Wit – The Advertiser, 5 January 1911, p.10. Support – Observer, 7 January 1911, p.43. Poetry – The Sun, 7 January 1911, p.8. Also local criticism – Northern Territory Times and Gazette, 6 January 1911, p.2; that the non-Chinese origin of the old flag was confirmed – The Advertiser,8 March 1911, p.14; and that most clothes wore that day were made by Chinese tradesmen – The Express and Telegraph, 3 January 1911, p.4.

[5] Chronicle, 4 March 1911, p.37.

[6] NAA: A1, 1912/10547, Petition forwarded to Mr Justice Mitchel, 22 March 1912. Those signing were noted to be either Australian-born or to have lived in the territory from 21 to 36 years.

[7] For a photo of Consul-General Tong Ying Tung see,The Sun,29 October 1910, p.1.

[8] “Supererogation” here meaning doing more than is strictly his duty – which he certainly was.

[9] NAA: A1, 1911/8882, Consul-General for China, Tong Ying Tung to Minister for External Affairs, 22 March 1911.

[10] NAA: A1, 1911/8882, Atlee Hunt, Secretary to Consul-General for China, 29 March 1911.

[11] NAA: A1, 1911/2525, Atlee Hunt to Government Resident, Port Darwin, 20 February 1911.

[12] NAA: A1, 1911/8882, Acting Administrator, J. Mitchell to Minister for External Affairs, 25 April 1911. [This letter is written on “Northern Territory of South Australia” letterhead with the “South” carefully typed over.]

[13] NAA- A1, 1912/10547, Notes of Deputation from Chinese Residents of Darwin, 6 May 1912.

[14 ]NAA- A1, 1912/10547, Notes of Deputation from Chinese Residents of Darwin, 6 May 1912.

[15] Observer, 11 May 1912, p.39.

[16] Observer, 4 May 1912, p.26.

[17] Observer, 11 May 1912, p.39.

[18] NAA: A1, 1915/7783, Departure from Northern Territory of certain repatriated Chinese, 25 March 1915, for a list of nearly 60 names; also a note from Atlee Hunt 19 May 1915. The Sydney Morning Herald, 29 July 1914, p.16.

For more on the repatriation see: Kate Bagnall, ‘“Repatriated to China June 1914”: How fifty-eight elderly Chinese men found their way home from Darwin’, Journal of Chinese Australia, issue 1, May 2005.