Unsurprisingly Chinese Australian characters pop up from time to time in 20th century Australian literature and just as unsurprisingly these are usually stock characters – a cook, a miner, a gambler or a gardener, but rarely a father, husband or son and even less likely a mother or daughter.[1] As a result little is revealed about the motivations or intentions of such characters. This is natural in works by authors who would have understood little, like most of their contemporary European Australians, about the motivations or intentions of their fellow Chinese Australians. People that most would not have felt, until deep into the 20th century at least, were in fact their fellow Australians.

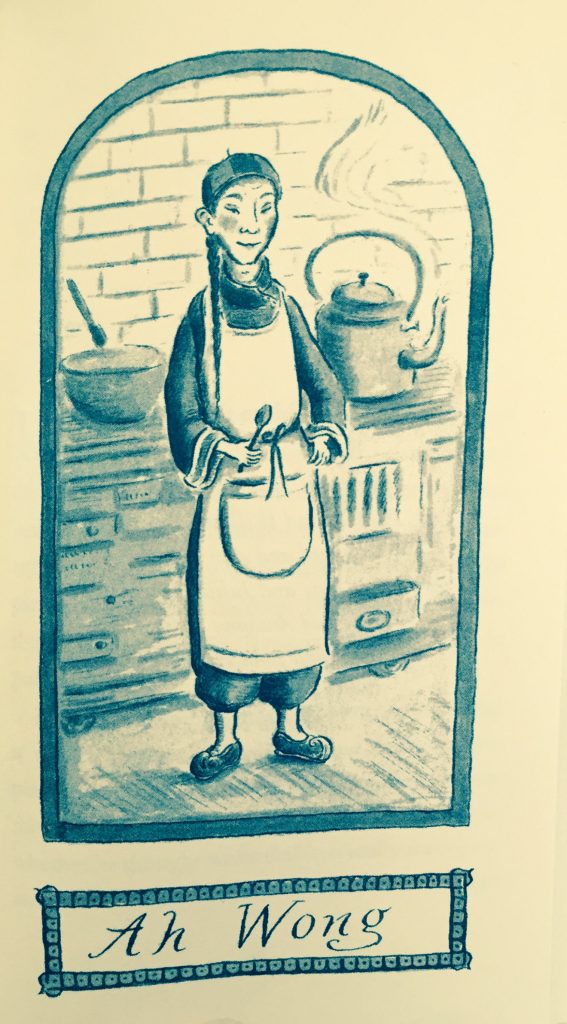

Nevertheless, writers often write from personal experience and something can be gleaned from their observations even when sieved through prejudice and ignorance. One such example it may surprise to learn is by P. L. Travers (the Australian-born author of the Mary Poppins stories) who wrote an interesting and for her times sympathetic account of her childhood association with a Chinese cook. Entitled simply Ah Wong, the story is not well known as Travers apparently produced it in a limited edition as a Christmas special in 1943 with the note: “This edition of Ah Wong is limited to five hundred copies privately printed for the friends of the author as a Christmas greeting.” A copy can be found in the NSW State Library however.[2]

The main character is Ah Wong, who takes care of the children of the family in rural Queensland that employs him, rejects their efforts to convert him to Christianity, and saves all his money. Travers grew up in rural Queensland and in all likelihood her family employed such a cook or certainly she knew families who did. Travers, child or adult, was ignorant as to why Ah Wong might save his money so earnestly, merely believing that he was saving to return to China – “All their lives they have saved their money so that they may have enough to take them home”. A very low income and a very high passenger fare it would seem. In reality of course men such as Ah Wong were supporting their own families in China, and if they grew old and were impoverished, they might receive assistance from district-based societies to pay their fare home. Though, unlike the ship Ah Wong takes seemingly full of only aged men, many younger men would also be visiting family in China, likely returning to Australia with their CEDT’s to work again after a few years.

After the death of her father Travers moved to Sydney and wrote for various journals and newspapers. The second half of the Ah Wong story has the girl from Queensland working as a journalist in Sydney where by chance she meets her childhood cook Ah Wong. Once again neither Travers or her journalist character has much idea of the motivations or life story of men like Ah Wong. What was known was the Chinese men traveling through the Port of Sydney by ship to and from China was common. That many by the early 20th century were old and that some returned to China for a final trip after a lifetime working in Australia would also have been general knowledge at the time. And this is what we are told Ah Wong is doing – taking ship in Sydney to finally return to China.

Only republished in 2014, Ah Wong is a fascinating addition to our Chinese Australian literature. However, while it can be categorised as “sympathetic” despite its stereotyping, this only highlights the limitations of sympathy without knowledge. For Travers, Ah Wong can only be written as an amusing two-dimensional character with none of the insights her Mary Poppin’s characters display. As yet the closest to such insights apart from The Poison of Polygamy already mentioned is not a work of literature but of oral history – the recently published South Flows the Pearl is a fine addition to much need individual insight into Chinese Australian history.

[1] Cheon the cook in We of the Never Never or Ah Soon the vegetable hawker in Henry Lawson’s Ah Soon: A Chinese-Australian Story for example. The great exception to this in Australian literature are the mothers, wives and husbands that appear in The Poison of Polygamy written by (not European) Wong Shee Ping.

[2] P. L. Travers, Ah Wong, New York, High Grade Press, 1943.