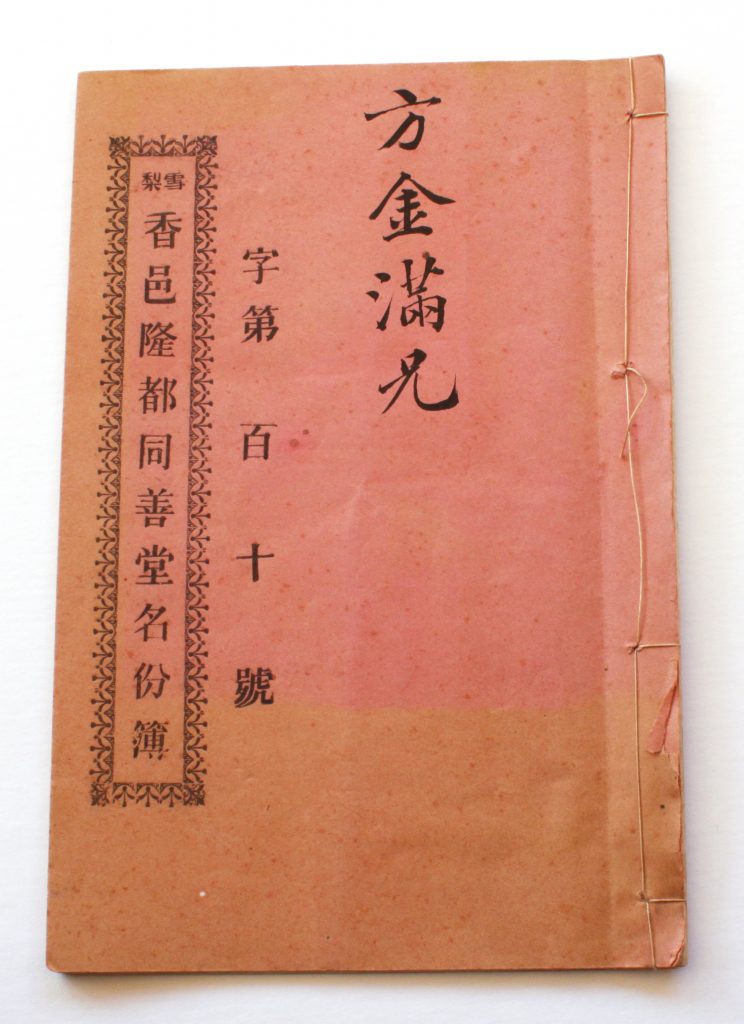

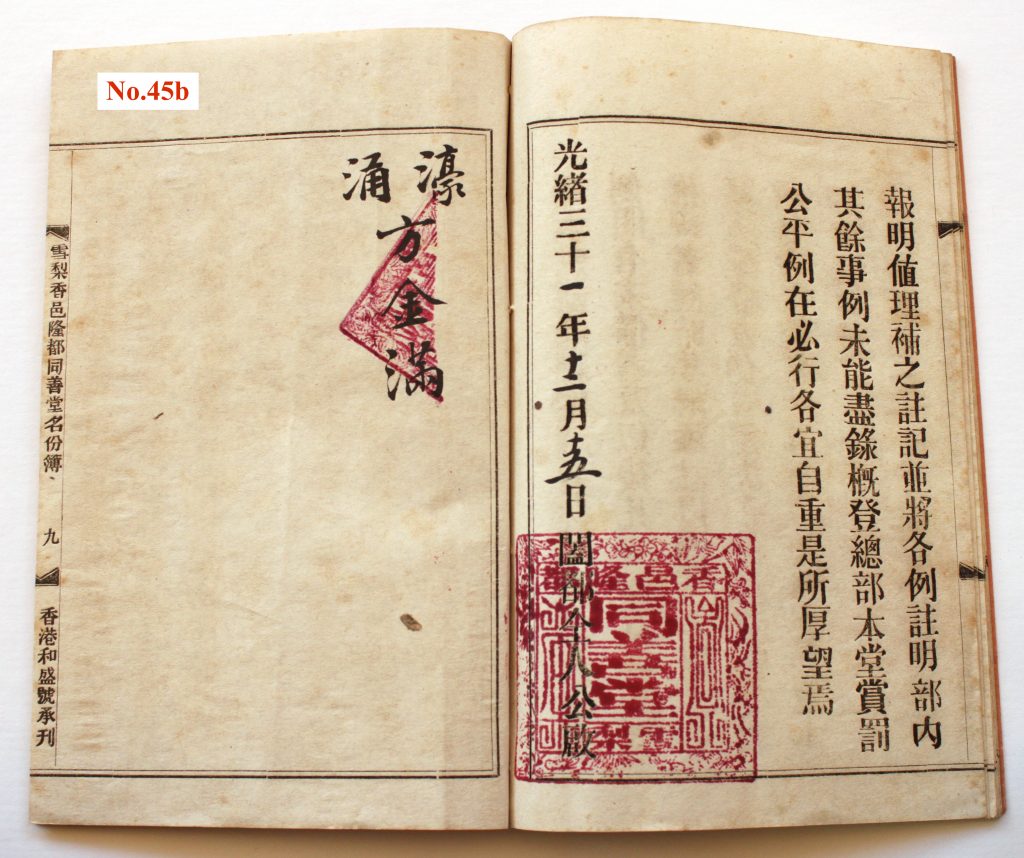

One of the fundamentals of Chinese Australian history is that for much of the period the concept “Chinese” is as much a made up one as “Australian”. By this is meant that just as many who arrived in the Australian colonies would have considered themselves primarily Irish or Scots, so too did those labelled “Chinese” by these same Scots or Irish consider themselves to be something more specific. Of course, as with everyone, considerations of family, village, dialect, region, nation or empire, not to mention religion, class or education, come into how we both identify ourselves or have an identity imposed on us by others. This membership booklet of Fung Kum Moon 方金滿 (Fang Jinman) from Ho Chung 濠涌 (Hao Yong) village is for an organisation of those originating in the south China district of Long Du (隆都) illuminates the significance of regional and language identity that played such a substantial role in Chinese Australian history.

The district referred to as ‘Long Du’ has a long history, part of Hsiangshan county 香山县 (now Zhongshan City 中山市) which was created as an official region in the 13th century. What most distinguishes Long Du and its approximately 80 villages from other Zhongshan districts is that its people speak a non-Cantonese language that re-enforced a sense of distinctness and fellowship both within Zhongshan and among Long Du communities overseas. The main overseas destinations of the people of Long Du being the United States, Hawaii, Peru, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.[1]

While a specific Long Du society of Sydney no longer exists (a more general Zhongshan one does), those of Hawaii and San Francisco still do. The purpose of these organisations is made clear in the objectives outlined in this membership booklet. It is very much a self-help association designed to pool resources and assist those originating in the Long Du district who find themselves in need and far from home. Membership is therefore defined by language and place of origin in Long Du. Once the fee was paid, entitlement to accommodation, passage money home, and assistance with immigration paperwork were all part of the benefits of membership.

Long Du was by no means the only or even the largest of the many districts of south China that sent people to Australia. But all of the many that did so – Taishan (台山), Kaiping (開平), Dongguan (東莞), Gao Yao (高要), etc. – organized themselves on the basis of their origins in these districts and counties or parts thereof.[2] This was done for similar self-help organisations as that of Long Du, but also for partnerships in stores and market gardens, for borrowing money to travel to Australia in the first place, for the all-important sending of remittance letters back home, and even for arranging marriages. As Sam Tin explained to a Royal Commission in 1891, he was denying membership of the Loong Yee Tong, not because it was a gambling society but rather because ‘as I do not belong to that part of the country they would not let me in it’.[3]

Only gradually did wealthier merchants after the 1911 revolution, and after them Australian born people of Chinese heritage, especially as Japanese aggression in China increased in the 1930s, begin to identify and organise themselves on the basis of being Chinese foremost. Village and district of origin however remained of great significance for many, even today.

[1] Williams, Michael., 2003, ‘In the Tang Mountains we have a Big House‘, East Asian History, vol. 25/26, June/December, pp. 85-112.

[2] Map of Pearl River Delta districts

[3] Report of the Royal Commission on Alleged Chinese Gambling and Immorality and Charges of Bribery Against Members of the Police Force. Appointed August 20th 1891. Government Printer, Sydney, 1892, p.117, line, 4665.

Thank you to Kira Brown in whose private collection this Long Du Society booklet remains. See: https://chenquinjackhistory.com/

Please contact me regarding joining.

Hi Diane – join what?

I’m looking for a Longdu speaker in Sydney to do a reading from English or Cantonese

Hi Diane

I do know a Long Du speaker – email me at: Michael.Williams@westernsydney.edu.au and I will ask him if he wishes to be contacted. Can you provide a little more information – nature of writing, how long, etc?

Cheers,

Michael

Hello Mr. Williams,

Thanks for posting this article about the LongDu Society Members. I am from the US and both of my parents are from Zhongshan. Our arrival dates from 1911 in Honolulu and some of us were in San Francisco. Would you be able to direct me to an microfiche or e-copy of this book? I’ve been finding bits a pieces of my ancestor’s foot prints and this could help us realize the extent of our familial diaspora.

Hi John – sorry of the slow reply. If you look at the bottom of the article you will see a link to the website of the person who owns a copy. You can contact them and they make be willing to scan you a copy.

Hi John

Just letting you know i have recently uploaded the booklet pages to my website

https://chenquinjackhistory.com/2025/05/15/1905-membership-booklet-for-the-sydney-long-du-association/

Cheers

Kira