Quong Tart (Moy Quong Tart – 梅光達) has featured in a number of objects in this series [See No’s 5, 8 & 23] and there are many reasons for this prominence in Chinese Australian history. Some of these reasons are undoubtedly due to his remarkable actions and strong character, many others however are down to the prejudices and selective memory that passes for Australian history.

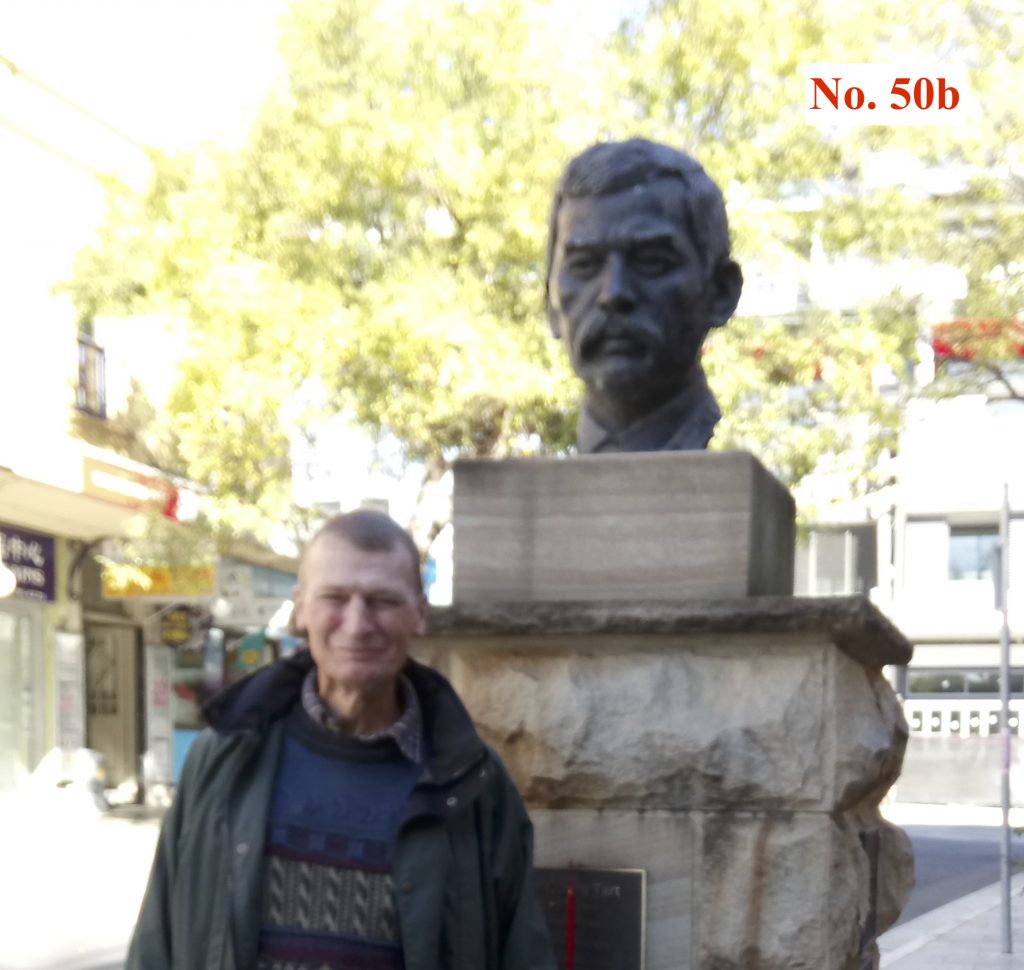

The memorial erected in 2000 on the road leading from Ashfield Station up to Liverpool Road on the route Quong Tart would have often taken between his home Gallop House (see No.5) and his City business represents this combination of factors perfectly. On the one hand the strong face of the sculpture conveys the intelligent businessman and bridge between cultures Quong Tart is well known to have been. Yet he was by no means the only, the richest, or the most influential of the numerous Chinese Australian businessmen in Sydney at the turn of the 20th century.

Sun Johnson, Phillip Lee Chun (see No.19) or George Bew among many other prominent members of the Chinese Australia community do not have their own statues. And while no doubt more deserving than many of his statued contemporaries of the mainstream community, Quong Tart’s also represents his easy acceptability by that same mainstream. The Scottish ballad singing owner of popular tea rooms in the Queen Victoria Building is an easily identified Chinese Australian that does not require any nuanced understanding or even any knowledge of the details of Chinese Australian history such as remittances, dialects or bones shipment, or of course racism and discrimination.

The erection of any statue to a Chinese Australian in 2000 was of course a significant shift in the symbolism that these material representations of Australian history typically embody. As such the Quong Tart head remains a lonely effort that has not been often repeated despite increasing academic efforts at researching and un-interring the nuances of Chinese Australian history. Efforts that have had as yet only limited impact on the embedded stereotypes that reside within mainstream Australian history.

Since 2000 one of the significant factors influencing this evolution has been the increasing number of migrants of Chinese heritage who have their own embedded stereotypes concerning Chinese Australian history. These stereotypes include a perception of an unremitting racism. A perception that led at one point to a widespread belief (on the popular Chinese language app Wechat), after a minor car accident damaged the pedestal, that the Quong Tart head was in fact the result of a racist attack that had left only his head remaining. This is a reminder that racism and fear of racism works both ways and that historians still have their work cut out.

What we choose to remember is as significant as what we forget in shaping the imaginary we call history.