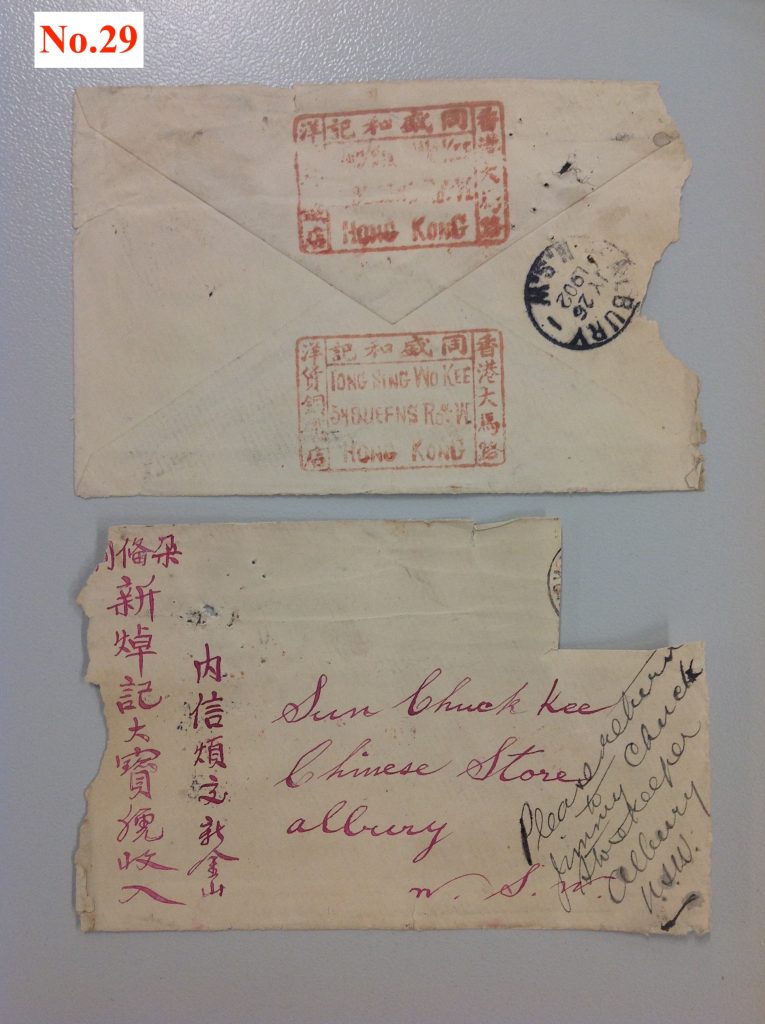

This now battered enveloped found in an old Immigration (then Customs) Department file is addressed in English to 新焯記 / Sun Chuck Kee at the ‘Chinese Store Albury’. The information in Chinese however includes the information that it is to be sent to ‘新金山’ or New Gold Mountain. In other words to ‘Australia’ using a term derived from the mid-19th century gold rush period when California was succeeded by the gold rushes of Victoria and NSW, thus becoming the Old Gold Mountain and Australia (or Victoria) the New Gold Mountain. San Francisco is still written today in Chinese as 舊金山 or Old Gold Mountain.

[The phrase “Gold Mountain” is in fact a now ubiquitous translation for the Chinese characters 金山 (gum san/jin shan) but was originally a translation choice over the more accurate if prosaic “goldfields”. This is a preference that sought to make exotic what for Europeans was considered normal – namely, rushing to goldfields. While an attractive term that is good for titles of novels and films it should be noted that it plays a part in that “othering’ of Chinese people that began in this period. Now firmly embedded in contemporary discourse it is used here and elsewhere with reservation.]

Such addresses and associated correspondence was of great importance to Chinese Australians, particularly for the remittances they usually contained. Remittances to family in the villages were a significant part of the lives of Chinese people in Australia before 1949. Early gold rush period remittances may have been in gold (dust then coin) but by the 20th century, bank drafts were more common. In such cases, a store owned by people from a related district collected individual remittances from its customers and if required a letter was written to the family by the store’s clerk to accompany the payment. When the Bank of China began to take over all remittances after 1949 it issued a standard form letter to accompany remittances that may have been modelled on that created by store scribes. Such a letter had 5 points: best wishes, write more often, let me know when received, have received your letter & tell how to spend the money in another letter.

The Kwong War Chong at 84 Dixon St, Haymarket Sydney (see No. 19), for example, charged a small commission on each remittance and consolidated them into a single draft drawn on the English, Scottish and Australian Bank in pounds sterling. The draft was then sent to the Hong Kong branch of the Kwong War Chong, where it was converted to Hong Kong dollars and then into Chinese dollars for the money to be sent to the Zhongshan County capital Shekki. The store’s branch in Shekki then distributed the money to the families, either by their collecting it or by it being delivered to the villages by the firm’s clerks. A receipt, which included a letter back to Sydney, would be signed and returned to the shop in Dixon St, where it was set up on a rack in the front window for people to collect.

This was the system used by most Chinese men working in Australia with small amounts to remit. It was a system that relied on family-like connections among people from the same village or locality. Something banks could not offer. Despite this, elements of mistrust could be present. A remittance customer once complained that his family had not received their money and accused Phillip Lee Chun of stealing the remittance. Phillip Lee Chun was sitting outside his shop at 84 Dixon St one evening, “taking the air” when, according to his son Norman Lee, he was suddenly struck on the head by a piece of “two by four”. The man later apologised when his family sent word that they had received the money.[1]

[1] Interview Norman Lee, Sydney, 25 September 1997 (5).

For a comprehensive and fascinating account of the remittance system see:

Dear China: Emigrant Letters and Remittances, 1820–1980

by Gregor Benton and Hong Liu, University of California Press, 2018