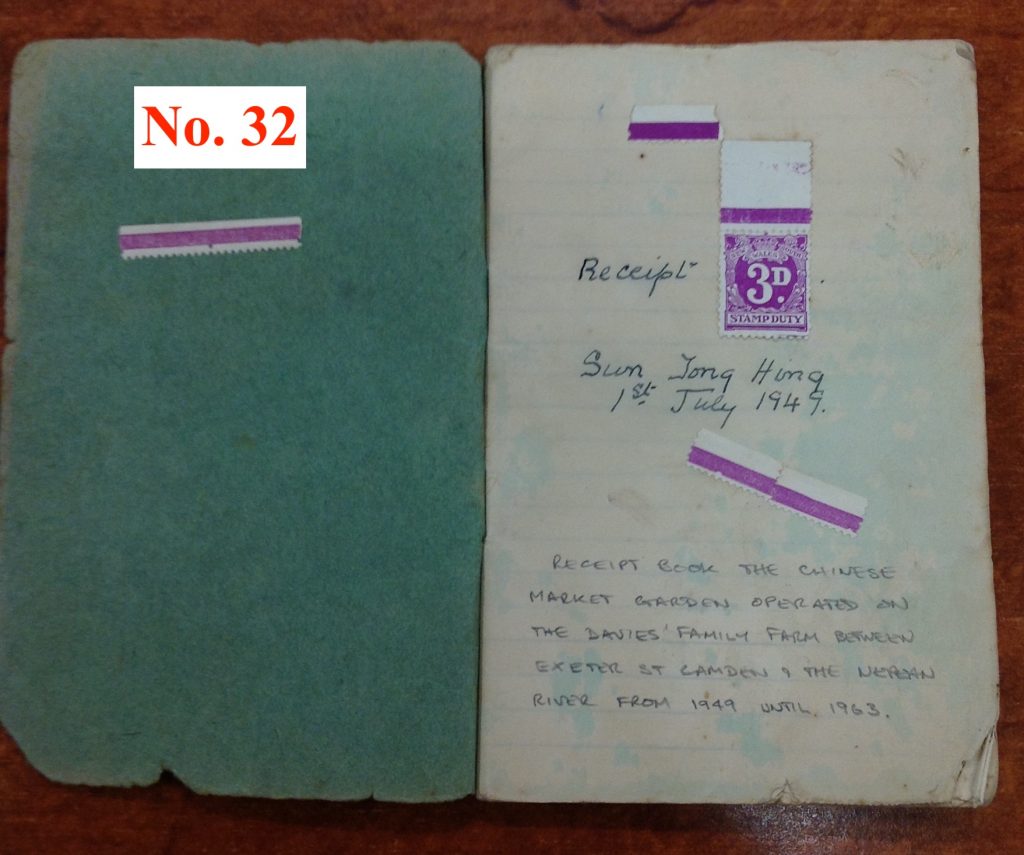

“Market gardener” comes just after “gold miner” as the prime stereotypical occupation of Chinese men in 19th and early 20th century Australia. Like all good stereotypes it has an element of truth, though at their peak perhaps only 30% of all Chinese men in Australia were actually working as market gardeners, and many vegetables were also grown by non-Chinese (though this is more difficult to estimate). Nevertheless market gardening was a major occupation and source of income. An income, as this rent book kept by Mary Davies of Camden shows, usually earned by leasing land for which a regular rent needed to be paid.

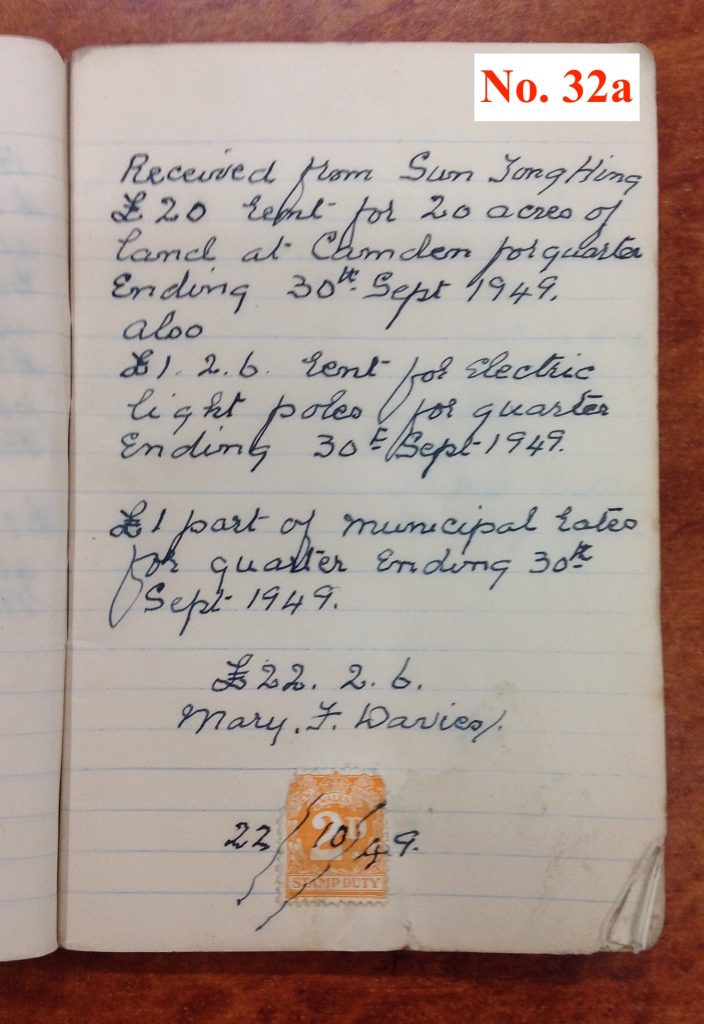

Camden, then as now, on the outskirts of Sydney was one of many locations where Chinese men could be found. They very often lived on the gardens themselves in very basic accommodation. The Camden rent book reveals that Sun Yong Hing and his partners (the most common arrangement) paid £20 a quarter in 1949 to lease the land, and in this case also paid for electricity and the council rates. The electricity was to run a water pump.

People like Mary Davies were often the main non-Chinese person some of these gardeners interacted with and they also often appear in the immigration files as writers of character references. Such references were necessary in the early days of the dictation test to enable people such as market gardeners to obtain a CEDT (Certificate Exempting the Dictation Test) so that they (legally barred from obtaining citizenship) could return to Australia after a visit to China. [See No.1]

Visits to China, perhaps every 5 or so years, were a common occurrence among market gardeners as they usually had family in their home village. They very likely had a wife and children, and ideally another on the way by the time they had spent a few years before returning to Australia. A new house (see No. 21) might also be the result of years of remittances sent through businesses such as the Kwong War Chong (see No. 19) in Sydney’s Haymarket. Perhaps even a diaolou (see No. 25) if they hailed from a district where such exhibitions of overseas earned wealth had become popular.

As with cafes, but not with furniture makers, market gardening became recognised by those administering the White Australia policy as a “Chinese” occupation. That is, it was seen as an occupation eligible for a substitute or an assistant from China who could be issued with a Certificate of Exemption (a more temporary form of the CEDT).

While the loophole in the White Australia policy for market gardeners was never as wide or as consistently managed as it later became for Chinese cafes (see No. 28), the many Chinese market gardens did also often serve as safe havens of a sort for another form of entry in the White Australia policy period – the smuggled and the deserter. In 1919 for example, a number of deserters (so called because they were employed on a ship as crew before ‘deserting’ to stay in Australia) were found to be working in market gardens around NSW. This was also true of the market gardens of Camden which were often raided. Despite offical efforts however such extra legal arrivals often worked successfully for many years, including for example Ah Tak whose share in a market garden when he was apprehended was said to be worth £500.[1]

See also: Chinese Market Gardeners in Camden: From 1899 to 1993 by Julie Wrigley Camden Historical Society

See also: A deserter’s fate: the Dictation Test at work.