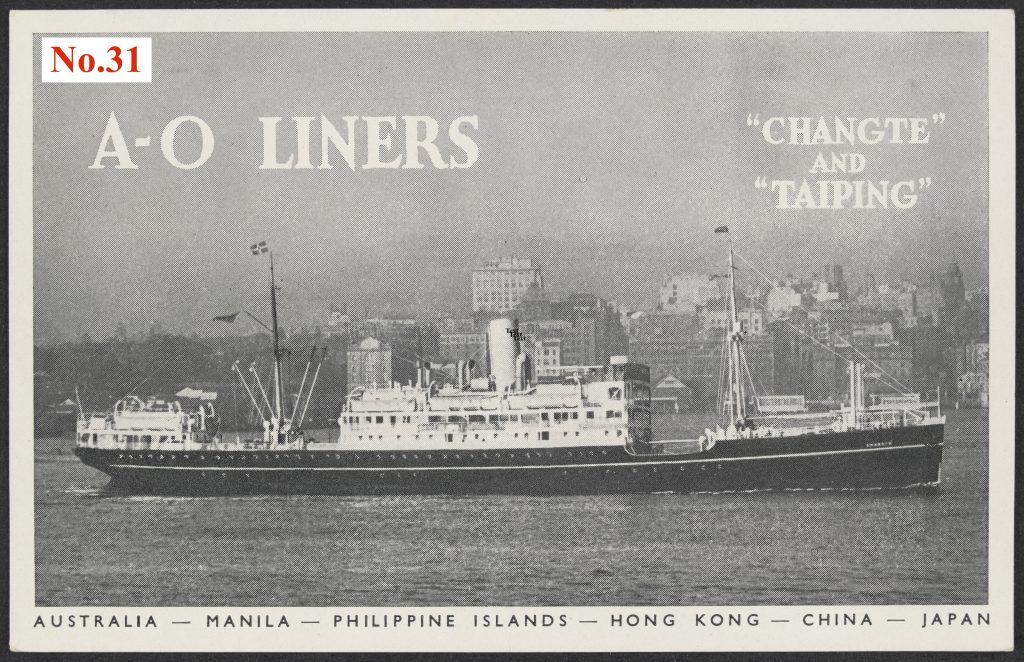

The sister ships named in this postcard were just two of many, some with the same names, that operated between Australia and its northern neighbours in the days when ships were the only means of arriving or leaving the continent. By the beginning of the 20th century, shipping firms such as the Eastern and Orient Line, and the Nippon Yusen Kaisha Line, operating the St Albans, The Empire, and the Nikko Maru, maintained Australia’s links to Asia. Later the Japanese line was replaced by the Australian-Oriental Line, which operated the Taiping, the Changte and the Tanda to Yokohama via Manilla, Hong Kong and Shanghai. These ships were much smaller than those used on the European routes. One of the larger ships on the run, the Tanda was 6,956 tons and was licensed to carry 258 passengers. In comparison, the Orion, which travelled to Europe via the Suez Canal, was 23,371 tons and carried over 1,000 passengers.[1] The total numbers of people involved were also much smaller with average arrivals and departures of Chinese people making the three week journey to and from Hong Kong varying from 1,500 to 2,300 a year in the first 20 years after Federation.[2]

The ship based nature of these links with Asia meant that in order to stem a perceived threat to a white Australia, a regime of ship searches, crew identification musters, prosecutions, fines, bonds and deportations was required. On arrival at Australian ports from Thursday Island, through to Sydney and Melbourne, customs officers would board ships and muster both crew and passengers for a careful inspection of their documents. Those most carefully inspected were non-Europeans, in particular Chinese. In addition, ships were thoroughly searched, not only for goods evading tariffs, but also for people. The well-known core of this effort from 1901 was the Dictation Test. [See No. 1] However, the key to restriction was not so much the reading of 50 words in any European language to create a “prohibited immigrant”, but that any shipping company carrying such a person was liable both to take them back again and to a heavy £100 fine. Shipmasters, shipping companies and their agents were thus the frontline in efforts to limit Chinese people arriving by boats such as those pictured in popular postcards.

As the S.S. Changsha in early 1938 sailed from Hong Kong for Australia’s eastern ports we have an interesting snap shot of who was coming to white Australia from China on the eve of the Second World War. On arrival at Australia’s most northern port, Thursday Island, the Customs officials telegraphed their colleagues in Sydney Customs with the names and variety of identification documents the passengers (Chinese) would present. These documents, examined on their first but by no means last muster before disembarking, ranged from passports to birth certificates, Certificates Exempting the Dictation Test (some expired) and even a Certificate of Domicile (issued in 1903), as well as a number transhipping to New Zealand. A total of 73 Chinese passengers (plus one “British of Filipino Race”), men, women and children and their ports of disembarkation from Cairns to Melbourne were recorded.

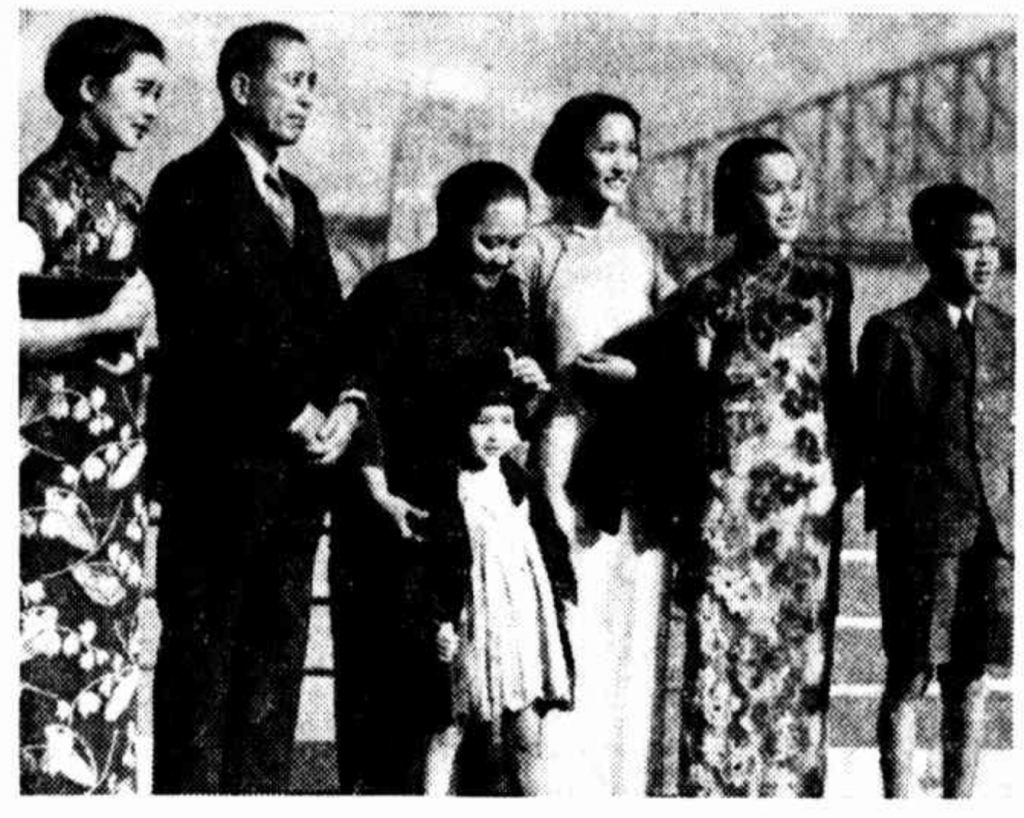

The Wong Yee family, which included two girls born in Strathfield, who had been away for 10 years were allowed to land after “telephonic instructions from Mr Peters” in Canberra and being “satisfactorily identified”. This last included the taking of handprints of the young girls for comparison with those on their birth certificates they, as Australian’s of Chinese heritage, needed to carry. Mr Joy Yow who had in his possession a Certificate of Domicile issued some 35 years previously was given only a three month Certificate of Exemption [see No.77], though now in his 60s he perhaps only planned a temporary stay in Australia. A total of seven with Birth Certificates demonstrating their Australian birth were also allowed to enter a white Australia, as was a Mrs Chen Au Shee, described as the wife of the manager of the China Emporium in Hong Kong and as a person of “superior standing”. Another described as of superior standing and also coming as a tourist was the “British of Filipino Race” Albert Cunningham, Chief Clerk of the Canadian British Railway. A final interesting arrival off the Changte in March 1938 was Mr Chang-Peng Ting the manager of the Swatow Hand-Work Manufacturing Co. who was bringing his wife and five children and Kitty Chen, this last described as a 15 year old “nurse”. This Sydney based company was still operating in the 1980s (making cane fly covers).[3]

Those not considered of “superior standing” included Low On who was entering as an assistant at Sydney’s Kwong War Chong [See No. 19] and Tye Sing who was allowed to enter as a “substitute” for Lim Joon under a policy designed to maintain the viability of some business’s and market gardens [See No. 21] designated “Chinese”. This was because few of the aged men resident in Australia before 1901 remained in white Australia having taken ships such as the Changte and the Taiping over the years to retire in their villages.

Source of the passenger snapshot: NAA: SP42/1, C1938/1868 – Coloured and Restricted passengers – ex-Changte, 8/3/1938.

[1] NAA: SP1148/2; Passenger lists, Outgoing 1929 & 1939.

[2] A. T. Yarwood, Asian Migration to Australia: the background to exclusion (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1964), Appendix III, Table 3, Arrivals and Departures, p.165.

[3] The Australian Women’s Weekly, 10 February 1982, p.95.