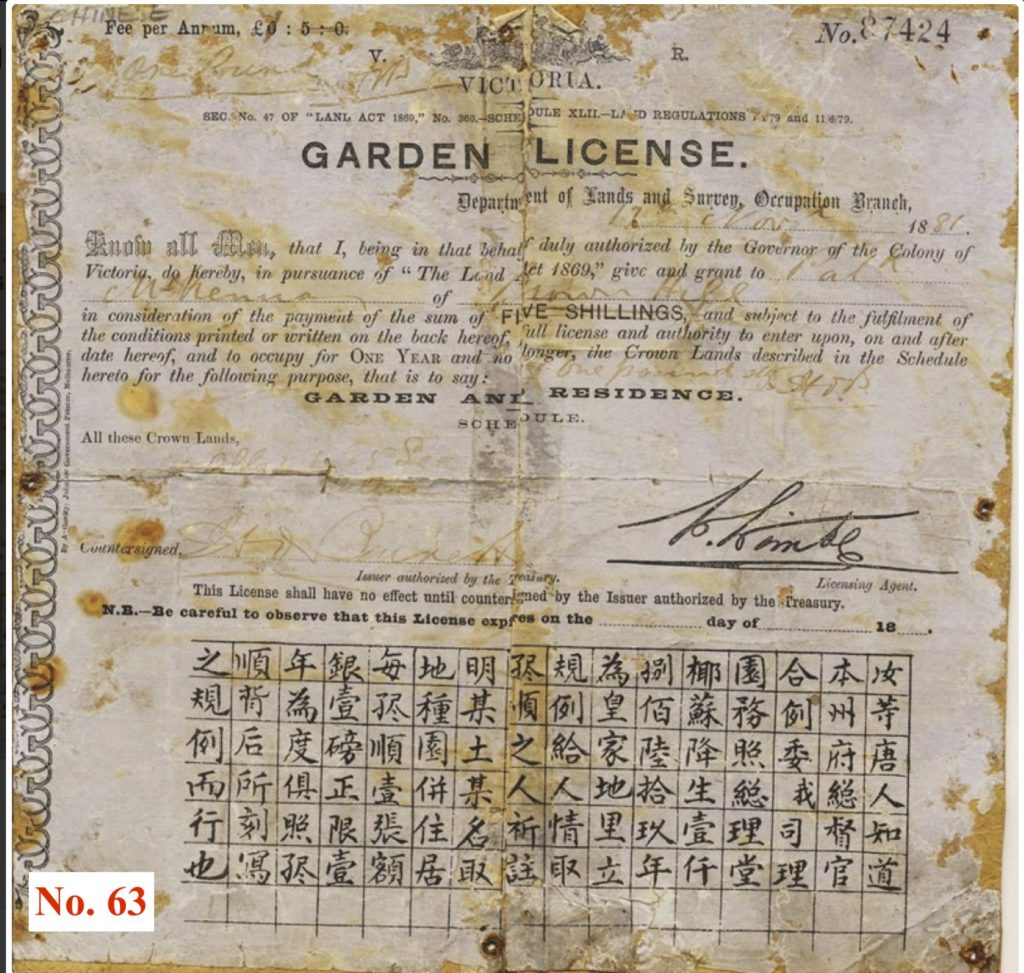

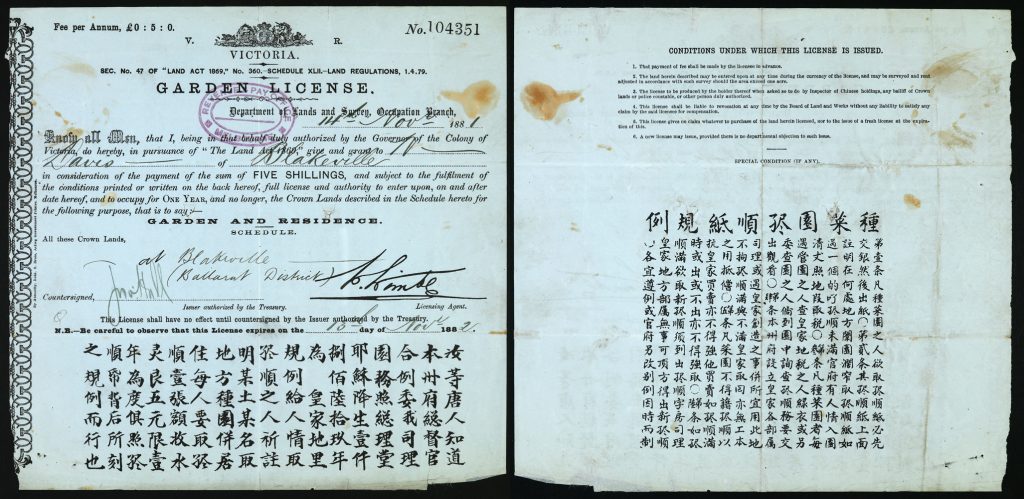

This bi-lingual licence issued to those wishing to operate market gardens in Victoria is representative of many things: – the high proportion of Chinese speakers that were market gardeners, or the difference between Victoria and NSW (the latter never issued licences for market gardening of any kind) for example. What it does not seem to represent is an attempt to discriminate against Chinese market gardeners as such. That is to say, not all official dealings with Chinese Australians were at the pointy end of discrimination.

Sometimes there was merely an effort to communicate with a largely non-English speaking population. In Victoria – the NSW government did not nothing similar – in the 1870s when “ ‘garden licences,’ intended chiefly to meet the case of the Chinese gardeners, who have hither to been in many cases occupying Crown lands without paying any rent” were introduced, the licences were printed bi-lingually in what was perhaps the first example of its kind in Australia.[1] Similar licences were apparently issued by the Northern Territory government (then under South Australian administration) but it is unclear if these also were bi-lingual.[2]

Even if the Territories’ licences were not bi-lingual it would appear that the Victorian and Northern Territory jurisdictions were the only ones in Australia that did issue official notices in Chinese. In the case of the Northern Territory this bi-lingual approach was inspired by a mix of having a high proportion of Chinese people resident there and increasing efforts to control and restrict them. In Victoria, with falling numbers of its long-term Chinese community it may have been a case of grudging accommodation. In any event the Mining Warden in the Northern Territory in 1880 stated that: “I have had notices in Chinese posted on the field” concerning his efforts to prevent conflict with European miners in a repeat of similar conflicts a generation earlier in Victoria.[3] Around the same time in Victoria the Central Board of Health, posted a “notice in Chinese re small-pox. —The notice had been posted at the Chinese camp.”[4] In 1882 the Palmerston (Darwin) Council was dealing with a series of letters from Chinese residents, presumably in English, but it consequently issued without fuss a notice in Chinese to enforce a ban on timber cutting in a particular locale.[5] Similarly the police in Victoria posted in 1884 a reward notice in Chinese regarding the murder of a Chinese man – though a passer-by was nevertheless shocked by the sight of Chinese writing.[6]

While these examples might indicate a degree of toleration and acceptance of differing language communities, cultural differences were never too deeply buried. Smallpox was a cause for concern in 1887 in the north when another notice in Chinese was distributed:

“Notices written in Chinese characters were posted round town on Tuesday commanding that all Chinese infected with small-pox should be reported to the police, under a very severe penalty for disobedience to this order. The police were compelled to do something of this kind because of the disposition of the Chinese to hide their sick countrymen.”[7]

Suspicion of carrying a disease such as smallpox was one thing, more general in its discrimination were the renewed Poll Taxes enacted in all the Australian colonies after 1888. Again it seems only the Victorian Collector of Customs, “had a notification put into Chinese hieroglyphics, to the effect that Chinese visitors to China” needed to register themselves else “they will not be allowed to return except on payment of the poll tax. The notice is to be posted about the Chinese quarters of the city.”[8]

Soon after, Australia was created by the federation of these colonies and their poll taxes were replaced by the Dictation Test. The new Commonwealth also produced relevant warning notices in Chinese (as well as Hindi). South Australia’s northern territory, however, would not be taken over by the Commonwealth until 1911 and in the meantime Palmerston Council in 1902 continued to communicate with rather than attempt to eliminate its large Chinese population, asking “that written notice in Chinese of new bye-laws be posted up”.[9]

[1] Gippsland Times, 17 February 1876, p.4.

[2] Northern Territory Times and Gazette, 2 Feb 1889, p.3.

[3] South Australian Register, 30 October 1880, p.6.

[4] Ovens and Murray Advertiser, 13 September 1881, p.5.

[5] Northern Territory Times and Gazette, 14 Oct 1882, p.3.

[6] Mount Alexander Mail, 11 October 1884, p.2.

[7] North Australian, 6 August 1887, p.3. [Europeans considered smallpox to be highly contagious while Chinese did not. Modern medicine sides with the Chinese.]

[8] South Australian Chronicle, 13 August 1892, p.10.

[9] Northern Territory Times and Gazette, 24 January 1902, p.2. See also: Ultra white faddists and the Qing Consul.