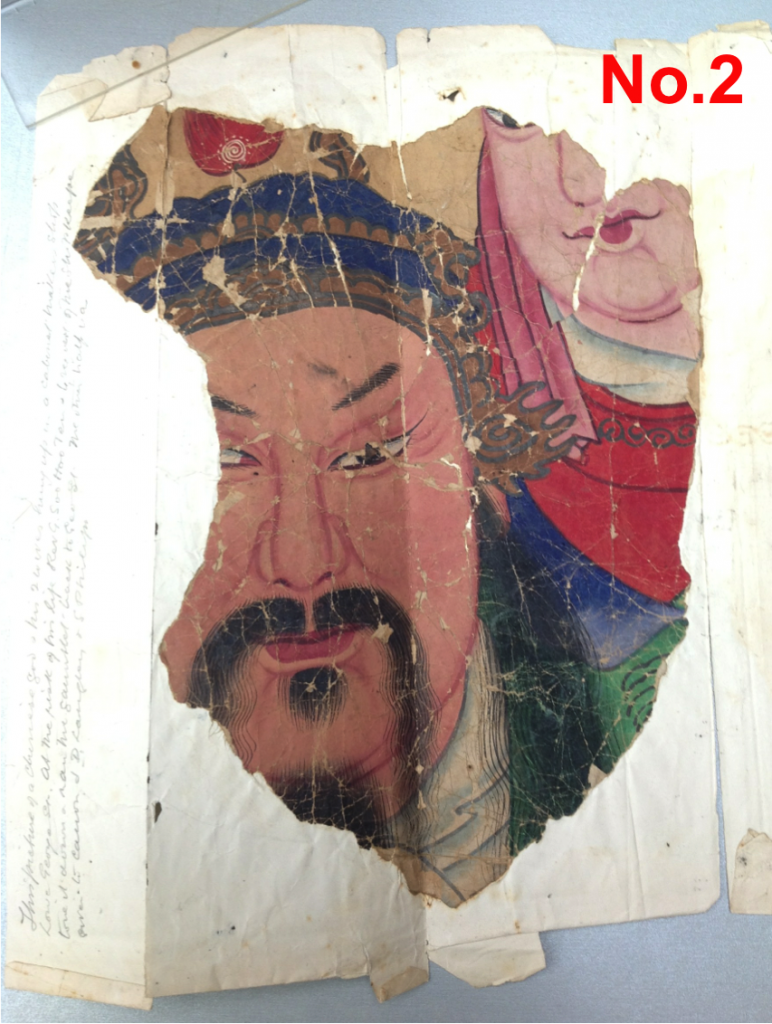

In a file carefully placed in a folder held in the State Library of NSW is to be found the torn remains of a colourful poster. Half of a bearded face, along with half a face of another beside him, can be perhaps identified as Lu Ban, an historical figure who became a patron of carpenters and builders. Such posters, whether of Lu Ban or not, were common in China, Hong Kong and in Chinese shops in many parts of the world, including early 20thcentury Sydney.

How this torn poster of a guardian god came to be in the NSW State Library is a story of religious intolerance and ignorance that was a common aspect of even middle of the road Christianity at the time. The poster itself tells us much – on the back of this torn ‘trophy’ in pencil is written:

This picture of a Chinese God and his 2 wives hung up in a Cabinet Makers shop Lower George St. At the risk of his life Rev G. Soo Hoo Ten at request of the shopkeeper tore it down and ran the gauntlet back to Geo St. The other half was given to Canon J D Langley at St Philips.

The Rev Ten had been born in Hoiping, Guangdong and converted to Christianity in San Francisco before coming to Sydney in 1881 as a tea merchant.[1] As a minister he worked among Chinese market gardeners for many years in the late 19thand early 20thcentury, and it is around this period that he presumably performed this deed at ‘risk of his life’. The reference to a ‘request’ on the part of the shopkeeper may imply a Christian convert wishing to remove an image of an ‘idol’ he could no longer tolerate regardless of the wishes of his fellow cabinet makers.

Cabinet making by Chinese workers was a common enterprise in the Rocks area of Sydney. Many of these workers would have naturally followed the gods they were raised with and a number of temples existed in Sydney and around Australia (see No. 10 & No. 18). However conversion to Christianity was also not uncommon and many churches maintained a ‘Chinese Church’ such as that of the Rev Young Wai at Foster St. In fact, as early as 1864 when a number of coffins were being shipped to China, it was remarked that many of the deceased had been ‘Protestant, Roman Catholic and Presbyterian’.[2]

Nevertheless, conversion to Christianity was more popular among the wealthy merchants, and Quong Tart and Dr On Lee, among others, were prominent in the congregations of the Anglican Chinese community. The market gardeners of Sydney preferring to remain ‘heathen’, as the Rev Ten would have put it.