For an example of the White Australia policy in action see:

1949-1959: White Australia policy survivors, refugees and others

Changes in the nature of the links of Chinese-Australians to China did not begin in 1949, and continued to develop in subsequent years. Certainly it was as a consequence of the anti-Japanese war that the small community of Chinese-Australians who were the survivors of the White Australia policy were supplemented by a proportionally significant group of wartime refugee stayers. While sponsored café assistants, market gardeners and other employees had been gradually increasing in numbers well before the war began, it was the post-1949 situation in China that created a refugee population in Hong Kong, including many people with Australian connections. One result of this situation was an increase in the numbers of people applying to enter Australia as sponsored employees, as well as in those smuggled into Australia on board ships who subsequently took up market gardening and other roles within the Chinese-Australian community.

Nearly 30,000 people of Chinese origin entered Australia in the 1950s, with over 10,000 of these doing so in the last two years of the decade, in part as the result of Malaysia joining the Colombo plan and consequent arrival of increasing numbers of students of Chinese background.[1] Over the same period over 1 million immigrants arrived from Europe. These numbers can be difficult to interpret not only because many people who consider themselves ‘Chinese’ came to Australia from places other than China but also because many people in the 1950s who were allowed to enter Australia from China as refugees, were in fact of European origin, particularly those known as ‘white Russians’.[2]

While many wished to leave China to come to Australia there were others among the Chinese-Australian community who were willing to go to China. Thus in this period when China was establishing a new order there were those who for ideological reasons returned to China to support the new government. Many who did so faced much suffering during the various campaigns and policy changes of the new China government. Conversely, within Australia anti-communist policies and fears also lead to much spying on the Chinese-Australian community, with ASIO and other government agencies suspicious of the political loyalties of many often simply because they were of Chinese origin. Photographs of those entering the Chinese Youth League were taken and some found their applications for citizenship denied after having attended this organisation’s premises to play table tennis. When King Fong was required to go to the Chinese Youth League to collect the pennies from the gas meter of what were his father’s tenants, he preferred to wear an apron so any cameramen would know he was merely entering for work purposes.[3]

**************

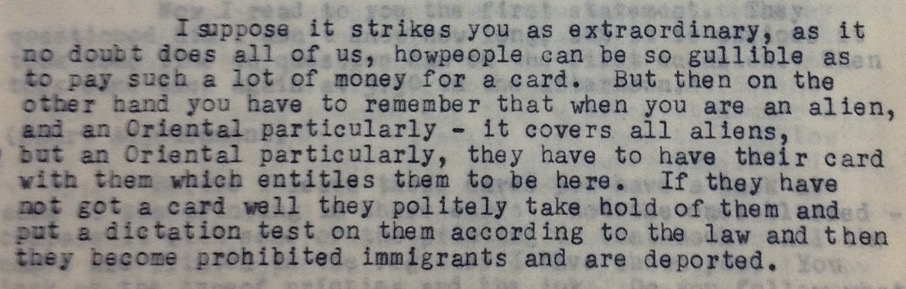

This is how one lawyer explained the situation of ‘Orientals” in Australia in 1954.

The context is the trial of a man accused of forging Alien Registration Cards for people who had arrived in Australia by being smuggled off a ship. The lawyer is explaining to the jury why anyone would be willing to pay large sums (£180) for such a card.

[NAA: C3939/2 N1962/7584, Regina vs Choy On, 12 July 1954 ]

**************

According to William Liu, efforts in 1950 to sign up Chinese members for the new Australia-China Society (later the Australia-China Friendship Society) failed when Immigration officials targeted those on Certificates of Exemption (needed to remain in Australia), with questions such as, “Do you belong to the Australia-China Society? Do you read China pictorials, do you read China Reconstruct?”[4]

Certificates of Exemption [to the Dictation Test] were required by all ‘non-Europeans’ who arrived in Australia after 1901, this, combined with the inability to apply for citizenship, kept this group in a legally vulnerable position. However, it was in the 1950s that the slightly more legally secure group, those who had been in Australia before 1901 and who had rights of residence but not citizenship, fell dramatically in numbers. This was because these oldest members of the Chinese-Australian community, many ‘single men’, though often in fact with a wife in China, had either returned permanently to China or were dying in Australia. As a result, having been declining in numbers over many years, it was in the 1950s that the last of the cabinetmaking workshops and many Chinese market gardens disappeared, partly due to lack of new workers. Conversely, Chinese cafes grew in number and geographical spread, due in part to Immigration Department policies regarding occupations for Chinese people.

In the 1950s there were still numbers of these aging ‘single’ men who had acquired a form a residency status by being in Australia before the Immigration Restriction Act of 1901. This meant they could reside in and even re-enter Australia after trips to China, but they could not become citizens, gain a pension nor bring their wives or children. After 1949 many of these men who could no longer work in the market gardens took up residence in single rooms such as above the Hang Tye in Thomas Street or the Say Tin Fong at 56-66 Dixon St.[5] Above the Say Tin Fong & Co. was to be found five floors, each partitioned into 18 rooms. Many of these men, over half of whom were from the Pearl River Delta county of Zhongshan in southern China, and the rest a mixture of people from counties also of the Pearl River Delta, kept up tenuous links with their families in the villages of these counties. They could receive letters and send every two months a 6 lb parcel of rice or tinned goods such as corned beef or ham. These parcels would be taken to the border of China by the Hong Kong post office to be delivered to the families. As basic as these food parcels were, in the poverty of China at that time such deliveries caused jealousies among the families. The men themselves earned the money to send these parcels by selling peanuts and spring rolls around the city streets.[6]

The ‘single’ aging men of the boarding rooms represented a continuing link with the villages in China. Say Tin Fong, on the other hand, who owned boarding rooms and whose son would continue to house the last residents until fire destroyed the building in 1985, represented the change the new government of China was bringing about. Say Tin Fong had originally gone to Fiji from his village in Zhongshan in the 1930s to join with his two brothers. Beginning as a carpenter, he worked at first for others, then ran a business manufacturing lollies, then a café, and then sold groceries. He married in 1935 a girl also from Zhongshan and his first son King Fong was born in 1938. The family spent the years of the anti-Japanese War in Fiji where the presence of American soldiers greatly improved the income of the business. In 1946 with the war over Say Tin Fong decided to move the family back to Zhongshan where he planned to buy land and live the life of a comfortable landlord.[7]

This was an aim many of those who left their villages in southern China shared and while the war disrupted these plans, its ending saw many return to rebuild villages and families that had suffered. Such plans were not usually disrupted by the civil war between the Nationalists and the Communists until 1949 as southern China was not directly affected until then, and when it was, the victory of the Communists forces was rapid and surprising. For Say Tin Fong, however, the tendency of events seems to have been clearer. It was in Sydney in 1946, while travelling from Fiji that he decided his plans of being a landlord would not be fruitful. Instead, with the help of the Chinese Consul Martin Wang he applied for and was granted a Certificate of Exemption as a merchant and so began his and his families long dance with the White Australia policy that would eventually see his son King Fong awarded an OAM.

That Say Tin Fong and his son were from Zhongshan County would be significant to their life in Sydney. The division of the Chinese-Australian community on the basis of their Pearl River Delta counties of origin, while not as significant as in the past, nevertheless continued to play a role. These included helping with communications to the villages, organising funerals, and assisting when necessary with immigration related matters. Thus the Zhongshan Association was run by its wealthiest members such as Willie Tong, David Narme, Mar Leung Wah of Wing Sang, a son of one of the Mar’s of the famous Hong Kong Sincere Co. Those with better English such as Norman Lee of the Kwong Wah Chong shop of 85 Dixon St acted as secretary. But while the various county or district associations remained significant, the divisions they once represented in the community were increasingly crossed, particularly among the business community. Harry Louie Fay, for example, of Inverell and a highly successful businessman in that area, would come down to Sydney and was able to purchase a share in the Nanking Café although he was from Zhongshan county rather than the Dong Guan county of its main owners.[8]

The role of the China Consul, Martin Wang in Sydney and the various merchants and those involved in the Chinese Chamber of Commerce as well as the district associations was crucial in maintaining cordial relations with the Department of Immigration. Immigration officers had enormous authority over the Chinese-Australian community with powers to investigate, initiate raids and ultimately to determine a person’s right to remain in Australia. To help smooth matters, regular meetings and dinners would be organised to set up informal channels of communication between groups that even in the 1950s did not always share a common language.

Most of these activities took place in Sydney’s Chinatown which by the 1950s had become so small in its Chinese population that Say Ting Fong & Co., which had a licence to import and export and was required to do so to the value of £10,000, preferred to export to the value of £9,000 and import only £1,000 as the demand for general Chinese goods was so low.[9] Irene Moss grew up in Sydney’s Chinatown, living above her parents tomato packing business at 47 Dixon St where, on the floor above, as in so many nearby buildings also lived many older Chinese men. She recalls rarely seeing a white face within the Chinatown area.[10]

A small change and an indicator of larger ones in the future came when not Chinese-Australian’s but mainstream Australian’s began to take up Chinese cooking as a new thing. After 1953 the Say Tin Fong & Co., a general grocery shop in Sydney’s Dixon St., following a spate of publicity, found itself selling more and more to non-Chinese customers.[11]

Thus the Chinese-Australian community was undergoing much change in the first decade of the second half of the 20th century as new members entered and old ones disappeared. New members and new activities demanded new organisations and in this period many new organisations were formed. Those founded in the 1940s such as the Chinese Seamen’s Union and the Chinese Youth League continued to operate. As did the Dragon Balls held at the Trocadero, begun in 1938 to raise money for China’s war efforts, they continued throughout the 1950s. That held in 1951, for example, was attended by over 1,700 people and raised money for local charities as well as China related causes.[12] There were also new organisations such as the NSW Chinese Workers Association,[13] the Australia-China Society in 1951 (later the Australia-China Friendship Society), the Chinese Women’s Association found by Phyllis Wang, the wife of the Chinese Consul-General in 1954, and the Chinese Club of Queensland in 1956.

The NSW Chinese Workers Association was part of an effort that arose at this time to ensure that the many employees trapped by their status as sponsored workers were also treated fairly by those that employed them. Under the continuing White Australia policy, employees needed to maintain a certain turnover to keep their status and therefore capacity to sponsor, this placed much pressure on their businesses and in turn could lead to their exploiting their employees. The common practice of providing meals and accommodation to workers, who often were also relatives, made calculations of wage rates and fair conditions even more problematic.

In 1956 came a major change when people with long-term residence in Australia could apply for citizenship. Coming even before the abolition of the Dictation Test in 1958, this marked the most significant single change in the White Australia policy since the Immigration Restriction Act was passed in 1901. Possible for ‘non-Europeans’ after 15 years (5 for Europeans) this extension of citizenship carried a demand for spoken English and the appearance of living as part of the Australian community that helped to preclude the older pre-1901 Chinese men and limited their claims to pensions also.[14]

Until this change in citizenship many Chinese-Australian’s despite working and residing in Australia for decades were not eligible for pensions, while others remained on temporary Certificates of Exemption (from the Dictation Test) that required them to remain in specific ‘Chinese’ occupations or to maintain businesses as certain levels of turnover to either remain in Australia themselves or to be able to sponsor and employ others. Thus Harry Hunt employed in his Merrylands shop a relative evacuated from Nauru during the war when threatened with deportation, and when the 20-year old King Fong’s father died suddenly in 1958, the son was required to take on the ‘merchant’ status of his father in order to remain in Australia himself and to be able to sponsor relatives that his father, Say Tin Fong, had already committed to. For those running businesses having ‘merchant’ status involved Immigration officers checking invoices and accounts every three months.[15]

In many ways this last decade was a final hurrah for the White Australia policy. The new Department of Immigration had taken over from Customs responsibility for policing prohibited immigrants and this change had created a more intrusive and active policing that saw raids and constant surveillance of Chinese-Australians. This attitude was often sustained by waves of fear of large numbers of ‘smuggled’ Chinese that appeared regularly in the media. At the same time a new Migration Act had finally abolished the Dictation Test and introduced a new visa based system that, while still very much aimed at limiting non-European entry into Australia, would prove administratively easy to adjust in this regard in the following decades. Even more significantly, changes to the citizenship laws for the first time in the history of Australia gave people from China and elsewhere who were non-Europeans the possibility of being more than temporary residents and continually under threat from Immigration Department officials. In the 1960s this possibility even became open to those who had arrived illegally.

Such changes were gradual however and many people of Chinese origin continued to be subject to an uncertain status:

“In October 1956, the Australian government officially acknowledged that many Chinese resident in Australia were unable to return to China, and created a new category for them, called ‘Liberal Attitude Status’, which entitled them to remain in Australia but not to bring their families from China. William Liu estimated in 1958 that around 2000 Chinese were in this situation of limbo, although they were, for practical purposes, permanent residents.”[16]

Many factors were driving changes to the White Australia policy and while the Chinese-Australian community was not itself active in this regard, one member, William Liu certainly was:

Liu, according to Palfreeman, had a huge influence on the organisation:

“I’d say we had quite a lot to do with Billy Liu…in fact, you could say he was an instigator of this organisation…No question about it…looking back on it and thinking from 1956 onwards, that the momentum established by Liu transmogrified into the Immigration Reform Association…”[17]

Questions to be asked/answered?

- What estimates are there of the numbers smuggled into Australia?

- Are there and stories of those who entered Australia illegally?

- Account of those who returned to China after 1949?

- Chinese Youth League activities?

- Details of the old men in the Chinatown dorms?

- Details of the membership and operation of various organisation?

- Accounts from Victoria/Melbourne and other parts of Australia?

[1] Department of Home Affairs, Historical Migration Statistics. Though perhaps as many as five times the number of students came to Australia privately as were sponsored under the Colombo Plan, see, Oakman, Daniel, Facing Asia: a history of the Colombo Plan (Canberra: Pandanus Books, 2004), p.179.

[2] For examples see, Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate, 24 April 1954, p.2 & Canberra Times, 9 April 1957, p.5; 6 January 1959, p.1.

[3] Interview King Fong, 26 August 2015.

[4] William Liu, interview with Hazel De Berg, 3 May 1978, MLMSS 6294/3, cited in Charlotte Jordon Greene, ‘Fantastic Dreams’: William Liu and the origins and influence of protest against the White Australia Policy in the 20th century (PhD, University of Sydney, 2005), p.190.

[5] Hunt, Stanley., From Shekki to Sydney: an autobiography (Broadway, N.S.W.: Wild Peony, 2009), pp.121-122 & interview King Fong, 26 August 2015.

[6] Interview King Fong, 26 August 2015.

[7] Interview King Fong, 26 August 2015.

[8] Interview King Fong, 26 August 2015.

[9] Interview King Fong, 26 August 2015.

[10] Irene Moss, “Chinese or Australian? Growing up in a bicultural twilight zone from the 1950s on”, in Morag Loh and Christine Ramsay, Survival and celebration: an insight into the lives of Chinese immigrant women, European women married to Chinese and their female children in Australia from 1856 to 1986 (Melbourne: M. Loh and C. Ramsay, 1986), pp.13-14.

[11] Interview King Fong, 26 August 2015.

[12] Sydney Morning Herald, 13 June 1951, p.8.

[13] Chinese Herald 22/9/1994

[14] Jordens, Ann-Mari, Redefining ‘Australian citizen’ 1945-75 (Canberra: Administration, Compliance & Governability Program, Research School of Social Sciences, Australian National University, 1993), p.14.

[15] Hunt, Stanley, From Shekki to Sydney: an autobiography (Broadway, N.S.W.: Wild Peony, 2009), p.112 & interview King Fong, 26 August 2015.

[16] William Liu, “The Chinese Residents in Australia”, 1958, MLMSS 6294/10, cited in Charlotte Jordon Greene, ‘Fantastic Dreams’: William Liu and the origins and influence of protest against the White Australia Policy in the 20th century (PhD, Univerity of Sydney, 2005), p.190.

[17] Interview with Tony Palfreeman, 16 September 2004, in Charlotte Jordon Greene, ‘Fantastic Dreams’: William Liu and the origins and influence of protest against the White Australia Policy in the 20th century (PhD, University of Sydney, 2005), p.221.