One of the most widespread leitmotifs in Chinese Australian history is the perception of Chinese people as a mysterious group whose communities and activities needed to be ‘interpreted’ by special investigations or self-appointed experts. Thus, an article in the Sunday Times 16 August 1896, entitled “A TRIP TO CHINATOWN” is merely one of a long series of similar efforts by sensation seeking newspapers. Only its subtitle, The Dens Described by a Lady Journalist hints that this one might be different. This however proves a false hope and not only is the article typical of its kind but its relentless sexism encourages the possibility that it was in fact written, or at least heavily edited, by a male pretending to be a female.

Regardless of the gender of the journalist this account of a visit to Chinatown is typical of the observations and judgements made about Chinese people living in Australia around the turn of the 20th century. Dens Described by a Lady Journalist runs through nearly every cliché in the European Australian guidebook of Chinese Australians. Thus, we get a ‘Chinatown’ right from the get go, murder, gambling, the need for a police escort, dismissive remarks about religion, opium smoking of course, vegetable hawkers and cleanliness, politeness, exotic cooking, mixed race, and to justify the ‘lady journalist’ angle, that great dread, the supposed Chinese desire for, and corruption of, white women.

A ‘Chinatown’ with its ghetto connotations rather than what it was, simply a poorer area of Sydney with a concentration of Chinese people and businesses, but nevertheless very much inhabited by non-Chinese people. The ‘Chinatown’ concept at this time having been imported from San Francisco and bringing a ready-made sense of the exotic. On arrival under police escort in this ‘exotic’ Sydney location – the streets near the then Belmore Markets (now the Capitol Theatre) – a murder is immediately alluded to. Though this crime appears to be merely for the purposes of adding atmosphere as it is unrelated to anything that follows.

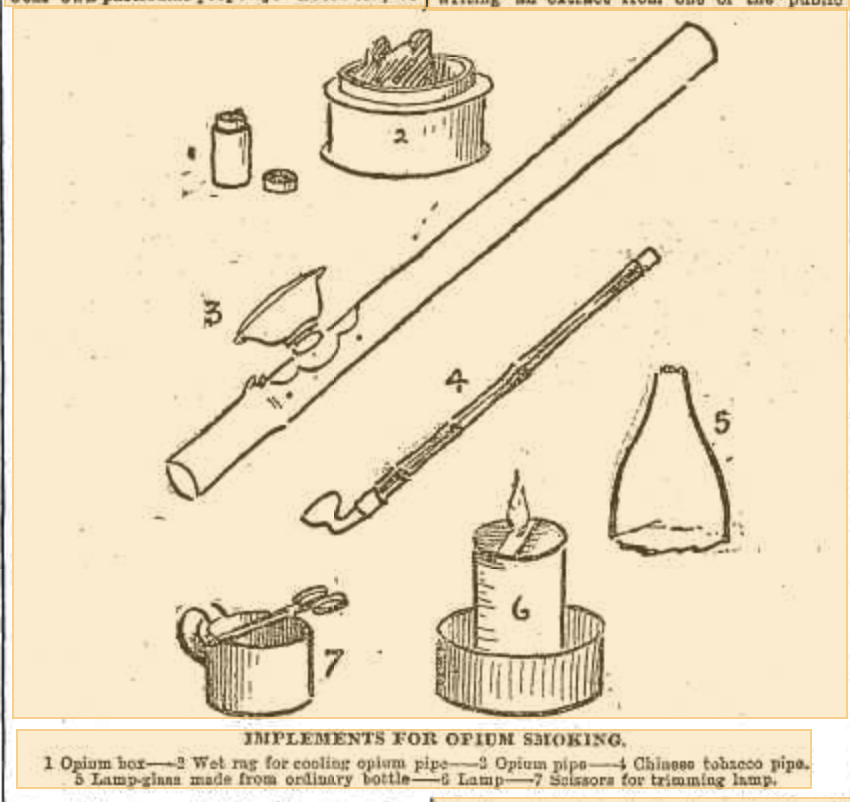

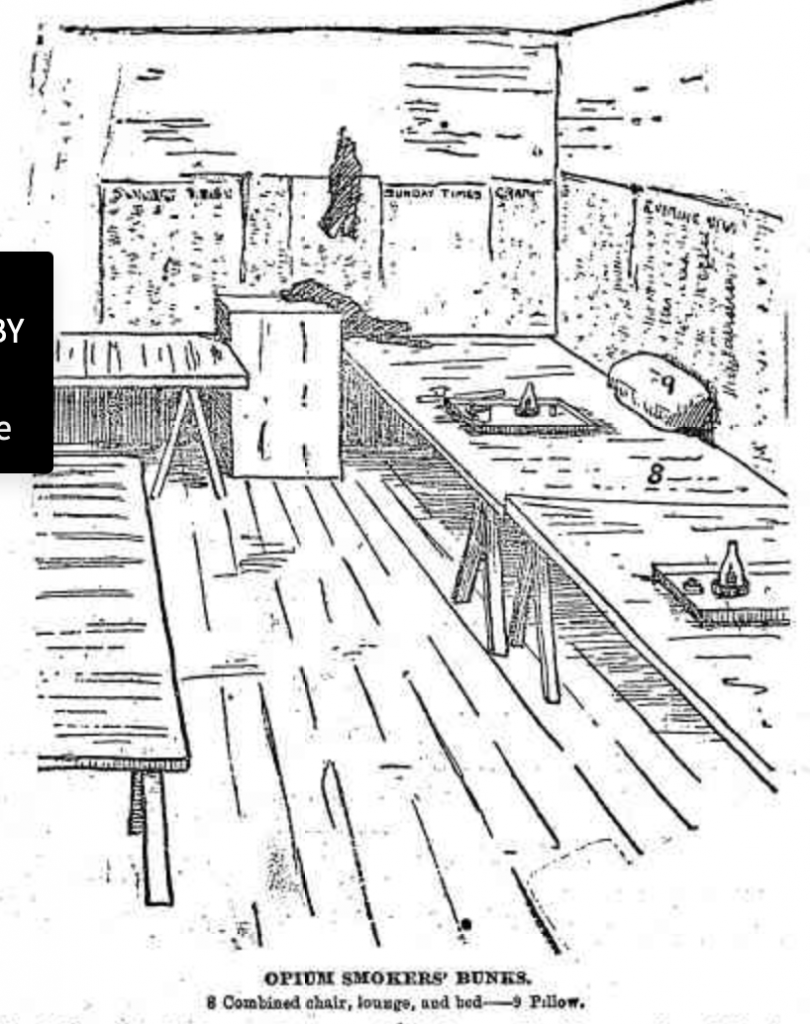

Next a gambling shop is briefly visited to add more colour to the investigation, though no mention is made of the fact that such places had a high proportion of European customers. After this a ‘Joss’ is described – that is a temple or at least a shrine to a Chinese god – in the kinds of dismissive terms that came effortlessly to late 19th century Christians. This is all preliminary to the arrival at an opium den, which while very much legal at this time would soon cease to be so. Legal or illegal such ‘dens’ held much fascination for newspaper readers and like gambling were often frequented by non-Chinese. In fact, two such non-Chinese customers are cited, including one who is allowed to make a prophesy that ‘an advance of civilisation’ would see opium ‘classified with tobacco smoking’.

Gambling and opium cover the two main vices attributed to all Chinese people at the time. These vices could be easily denounced as ‘wrong’ by those readily inclined to make such judgments while reading a newspaper. More difficult to evaluate was the success of Chinese people at selling vegetables to those same readers, their well-known politeness when doing so, the deliciousness of their food, and the tendency of white women to marry them and produce children of mixed heritage. All these are dealt with in a manner typical of the period, including damning with faint praise and the introduction of carping asides. Thus, the recognisably ‘fine cabbages and cauliflowers’ are kept in conditions that makes the writer ‘thankful for the efficacy of boiling water’. The politeness is perhaps due to simplicity. While the cooking is undoubtedly ‘nice’ and ‘dainty’ looking but only leads to ‘hastily swallowing a eucalyptus lozenge’. Finally, to ‘a rather striking-looking woman, a half-caste Chinese with a suggestion of Semitic origin’ is attributed what cleanliness is apparent.

It is the appearance of this woman of Chinese/European heritage that sets off a puzzled denunciation of mixed relationships. It is well known apparently that ‘they [Chinese men] prefer Europeans speaking generally’ while that they are ‘most kind and considerate’ is dismissed rather weirdly ‘as but the outcome of the Asiatic philosophy’. It follows from such a flawless argument that any association with ‘white women’ must be ‘prolific of the utmost degradation’. The prejudiced ranting and confusion of emotion with logic carries on for a while more but to no better effect until the journalistic investigation reaches its denouement when a real live white women or girl in this case is found in the clutches of the Chinese.

The readers are obviously not ready for any realistic account of the vulnerability of young women in their society and instead are presented with a foolish girl whose loving family will take her back in a heartbeat. All that is necessary is a few words from a gruff but kindly policeman and a ‘women who understand women’ and her escape is assured. Any support or assistance shown by the Chinese man is mere entrapment and so the basic goodness and sanity of white society is maintained. The readers of such articles were presumably titillated and shocked enough to feel safe in their world while not actually learning anything to disturb their prejudices. If there is anything wrong in the world it must be the fault of the Chinese. Such writing was common and served to reenforce the stereotypes and justifications for the then evolving White Australia policy. It would be nice to feel that such pitiable journalism was the preserve of the late 19th century only but anyone who still reads newspapers, let alone more modern forms of media, knows this is sadly not the case.