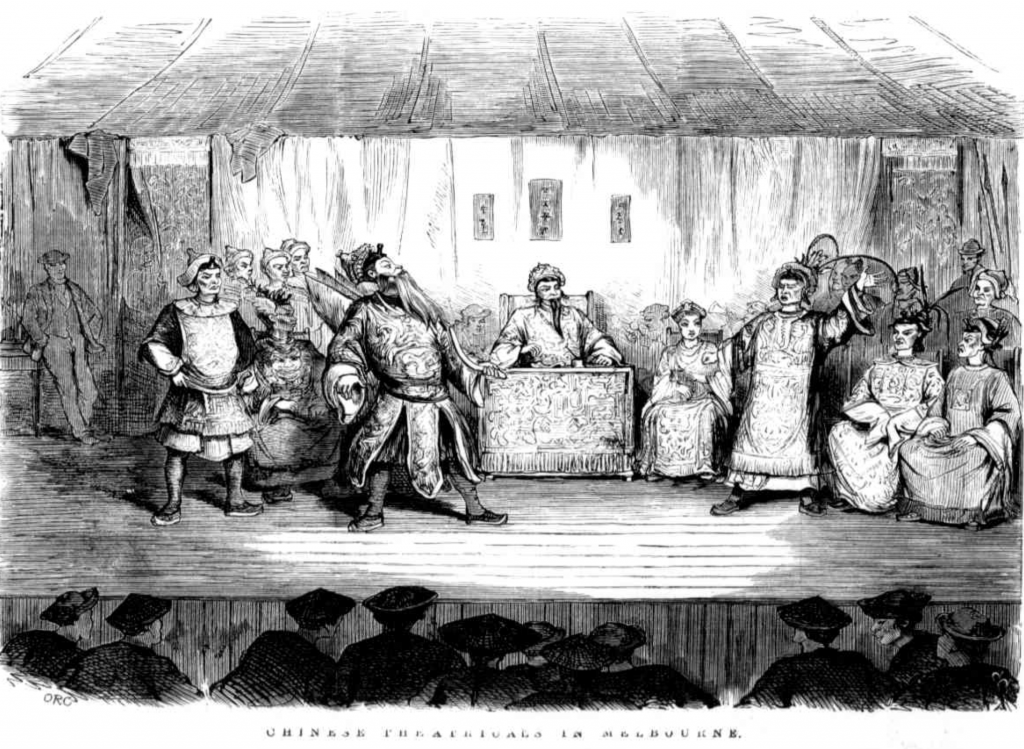

Much of the history of Chinese Australia seems about hostility and racism, or attempts to subvert and overcome these negatives. But at one point in the history Chinese people were simply exotic arrivals from a foreign land. Before the (white) locals could begin adopting stereotypes or making up reasons to reject those who were different they were confronted with people who were different. There are hints of sheer honest amazement at Chinese culture and civilization piecing through the narrow assumptions of British/Christian superiorly in some of the accounts of Chinese Opera in 19thcentury Australia.[1] But outside these examples the dullness of a pervasive smug condescension holds sway.

However, early in the NSW goldrushes the small, relatively isolated settlement of Bathurst, only a generation after it war with the surrounding Aboriginal peoples, found itself presented with some 150 Chinese men walking to the nearby goldfields.[2] This well organised company were the cause of much excited for the locals and crowds of them came to the camping area to gawk at the newcomers. An account of this spectacle gives us some idea of how things were as two groups of strangers first met without yet any history of antagonism or the need to throw up self-justifying prejudices.

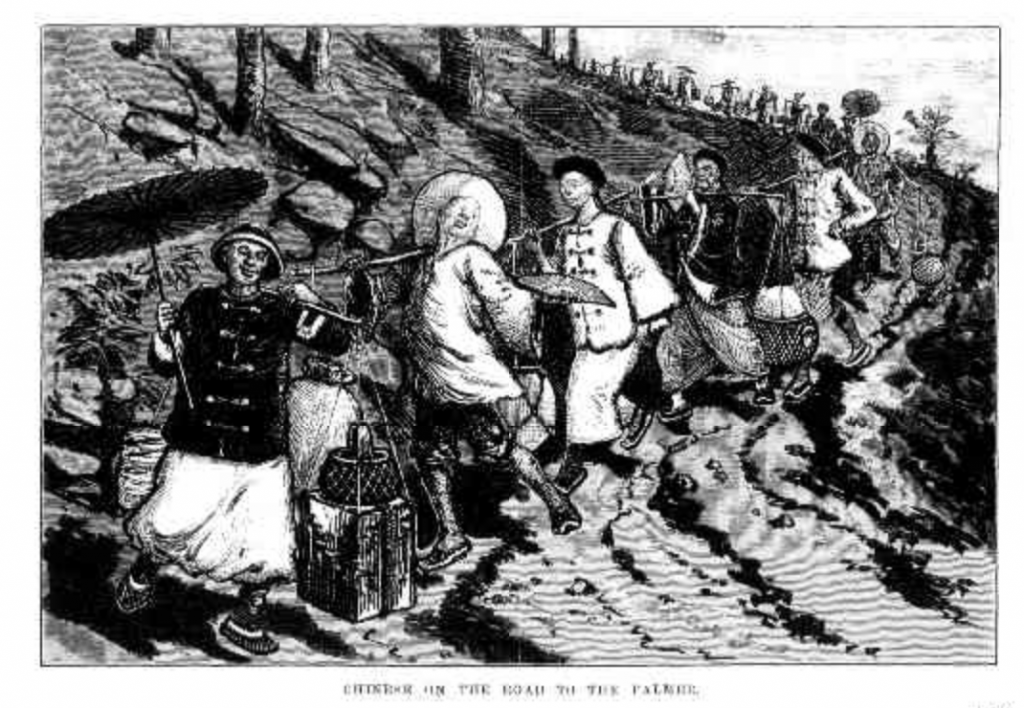

Our diggings promise to become the sites of a series of Chinese colonies. A few days ago a second batch of the sons of the Celestial Empire arrived in Bathurst, consisting, as nearly as we can guess, of about 150, and proceeded to the camping ground of their predecessors, where they pitched their tents, spread their mats, and commenced cooking — , favourite pastime apparently, which, together with eating, seems to swallow up the whole day. Amongst their number we perceived several rather ancient looking pig-tails, who, in all probability, have come to deposit their bones in Australia. Their canvass village has been a favourite resort for the townspeople, who have thronged in front of their tents to witness the novelty of their proceedings, amongst which the expert use of their chopsticks was not the least amusing. Their economical use of firewood was another circumstance which called forth the astonishment of the visitors, who saw that by digging small holes in the ground, with ventilation only in front, that about as much timber was consumed in boiling and stewing for 150 as would cook a meal for a single family, after our own fashion. There was the usual display of fans and purses, and other trifles for sale, but the exorbitant prices asked reduced their traffic almost to nil. On Monday last they struck their tents, and trotted off to the westward with their stock of domestic utensils, mats, and bedding, slung upon poles.[3]

There is little here of the fear and loathing or the heavy patronising tone that would become commonplace. On the other hand, there is also no hint that practices which, for example, would reduce the consumption of firewood to an extraordinary degree might be worth imitating. The arrival of this group is an interesting spectacle but it is not one that could impinge upon the habits and prejudices brought ready made from Europe. The scene is set for that ‘othering’ that would make up so much of subsequent Chinese Australian history.

See also Bathurst 8

[1] For example, Local Intelligence – Chinese Opera, Ovens and Murray Advertiser, 7 March 1863, p.2, where the critic is both ‘astonished and pleased’. For more on Chinese Opera in Australia see Smoking opium, puffing cigars, and drinking gingerbeer: Chinese Opera in Australia.

[2] See, Stephen Gapps, Gudyarra: The First Wiradyuri War of Resistance — The Bathurst War, 1822–1824.

[3] Bathurst Free Press and Mining Journal, 30 July 1856, p.2. Thanks to Juanita Kwok for spotting this gem quoted in her excellent thesis, Juanita Kwok, The Chinese in Bathurst: Recovering Forgotten Histories, Doctoral thesis, Charles Sturt University, Bathurst, 2018.