How do you lose a gift from the Emperor of China? By hiding it in plain sight.

Pictured is a large character inscription – 仁歸海瀛 – “Benevolence comes from across the seas” – gifted to an Adelaide committee in recognition of their generosity in donating towards famine relief in 1889. That Adelaide had such a committee was the result of a network of Christian missions operating in China. An even more devastating famine in the 1870s had resulted in a mission-based relief movement that made appeals for funds around the world, and places such as London, Adelaide and Melbourne had responded. This first effort had not been done in co-operation with the Qing government, however subsequent efforts were.

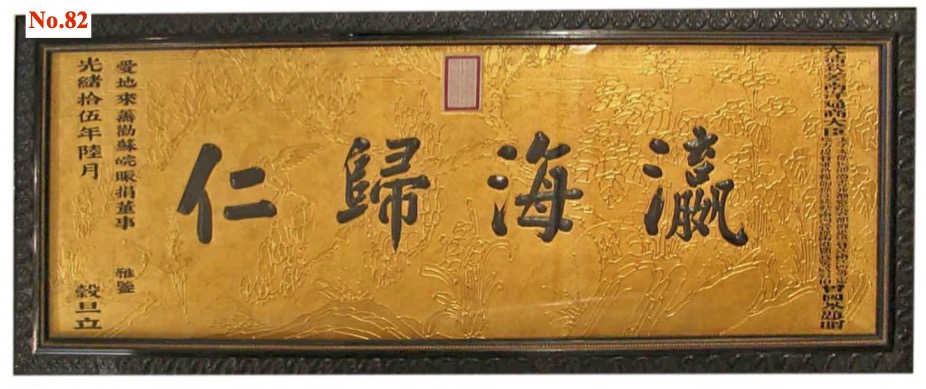

Thus, when famine again struck northern China an Adelaide famine relief committee was formed in 1888 and its efforts were rewarded with this character plaque described at the time as ‘a large tablet of wood 5 ft. 6 in. long and 2 ft. deep, deeply gilded, and containing an inscription in the Chinese character in heavy black lacquer upon a dead gold ground.’[1] The gift is ascribed a direct from the Emperor but actually bears the seal (in both Chinese and Manchu) of a high official, the Minister for Southern Trade.

Headed by the Mayor of Adelaide the committee included a number of prominent citizens including Yett Soo War Way Lee who had arrived in Australia in 1874 and by 1889 was a wealthy Adelaide merchant married to Annie Way Lee, a local woman, and with an established family. Perhaps the inclusion of a Chinese speaker inspired this special recognition or perhaps it was the recent visit by the Chinese Commissioners, whatever the reason the Adelaide committee was a rare instance of direct contact with the government of China at that time.

Such an object is rare and in Australia extremely rare. Yet recently neither the City of Adelaide, nor the South Australian Art Gallery nor the South Australian Museum knew anything about it. In fact, the consensus was that it had been “lost”. Lost until a posting on Facebook triggered a memory of its being on display at the Adelaide Migration Museum. A museum that readily confessed to having this wonderful object in storage.

Is there any reason therefore to claim the object was ‘lost’ rather than simply blaming ignorance? The journey of this Imperial gift reveals something of the problem. Originally it was hung in the City of Adelaide Council Chambers for an indeterminate time before being relegated to council storage until the 1970s when it was apparently decided to sell it off. Fortunately, the SA Art Gallery purchased it from the dealer who had it, only to give it to the newly created Migration Museum in the late 1980s.

Despite this relative neglect the plaque was well preserved and was displayed for a period, although its full context remained a mystery. Thus, the relegation of a valuable “Chinese” object to an institution centred on migration is problematic. That the gift of one government to another based on an early instance of intergovernmental support can only be seen in terms of “migration” is indicative of a fundamental issue in Chinese Australia or any “ethnic” history in Australia. This is the perception that only “white” history is real or core Australian history and anything else is marginal, parallel or “migrant” history. The result is that such an object could not easily be seen as simply part of the history of Adelaide still less of Australia.

Much is lost in this conceptualisation as the “loss” of this Imperial tablet to Australian history demonstrates.

See also: Benevolence Returns from across the Seas by Michael Williams & Yuexiu Shen, History SA, No. 273, January 2023, pp.9-13

For many more objects of the 88