Undoubtedly the “goldrush” outshines most other – market gardeners excepted – elements of Chinese Australian history. Certainly, the thousands of workers who arrived before the gold rush, generally referred to as Amoy indentured labourers, often find themselves reduced to at best a footnote. (See No. 59) To see a memorial especially devoted to this group is therefore to be commended. All memorials pretend to say something about the past while in reality saying a great deal more about the present of those who are funding it. What does this memorial in St George, Queensland say about the present? (See also No. 47)

While this object represents an historical group that deserves greater recognition it also highlights the increasing number of interpretations and re-interpretations of Chinese-Australian history – most with limited input by historians. These re-interpretations include but are by no means limited to Young’s Lambing Flat Festival, Tasmania’s Trail of the Tin Dragon, Sydney’s Celestial City exhibition, Ballarat’s Open Monument, Rookwood Cemetery’s Chinese Gold Miners memorial, and a recent film on Chinese Australian history entitled The Change.

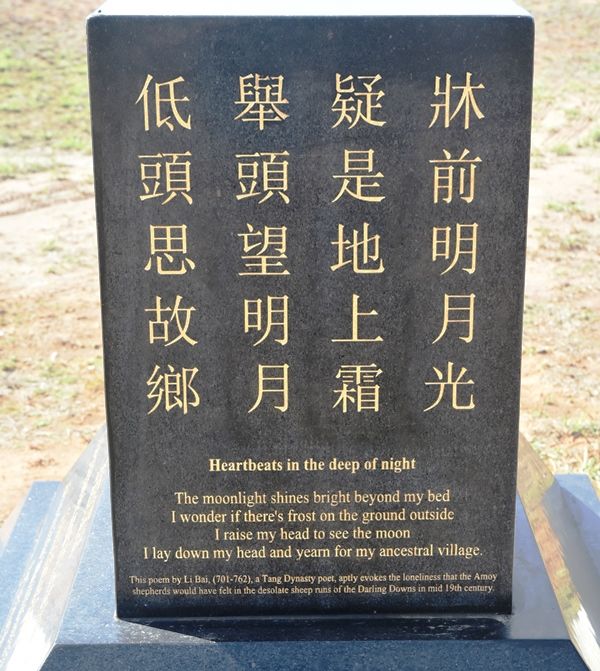

The memorial’s inscription paints a picture of hardship and unrewarded labour of those leaving a “famine in Amoy” or working in “coolie” gangs and failing to return home because they “never earned enough”. “Most, if not all, never saw their families again. They endured a lonely and impecunious life to the end.” This all paints a very grim picture which ignores the many intermarriages, families, and returns (not to mention the fact that the so-called “coolie” gangs would have been Cantonese people with a very different story), that also constitutes the history of this group. The unrelenting negativity reflects a history of the overseas Chinese much favoured by the Chinese Communist Party which prefers its history without nuance.

This is not to say the memorial was dictated by Beijing as there are undoubtedly many contemporary Australians who favour this kind of story-telling over historical analysis in order to promote their favourite modern perspective. Thus, the highlighting of the diversity and freedoms of contemporary Chinese Australians in contrast to the past is not unusual. But the question can be asked: Does pretending the past was unreservedly negative help us understand it? Let alone contribute to understanding the present?

The men who came as shepherds on contracts through the port of Amoy (Xiamen) were brought by those determined to pay as little as possible for those they needed to do the hard work so they could reap the maximin profits. Racism, discrimination, exploitation and hardship were all part of the mix. This is a glimpse of the past that perhaps does not provide the kind of self-satisfied contrast with ourselves that leads to funding for memorials. Perhaps those who actually lived this history deserve better.

For more on the Amoy Shepherds see:

Responses and Reactions to the Importation of Indentured Chinese Labourers

by Maxine Darnell