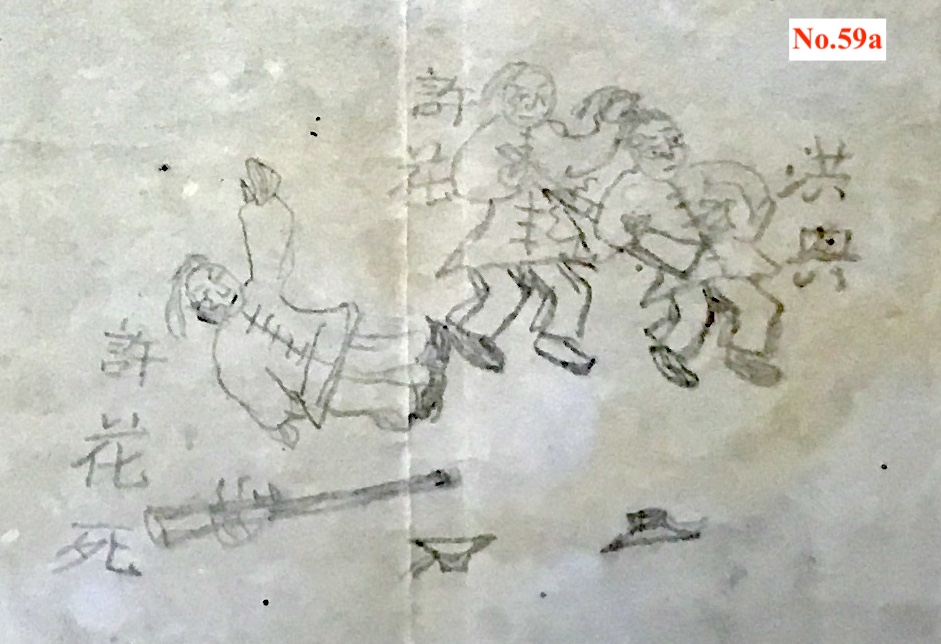

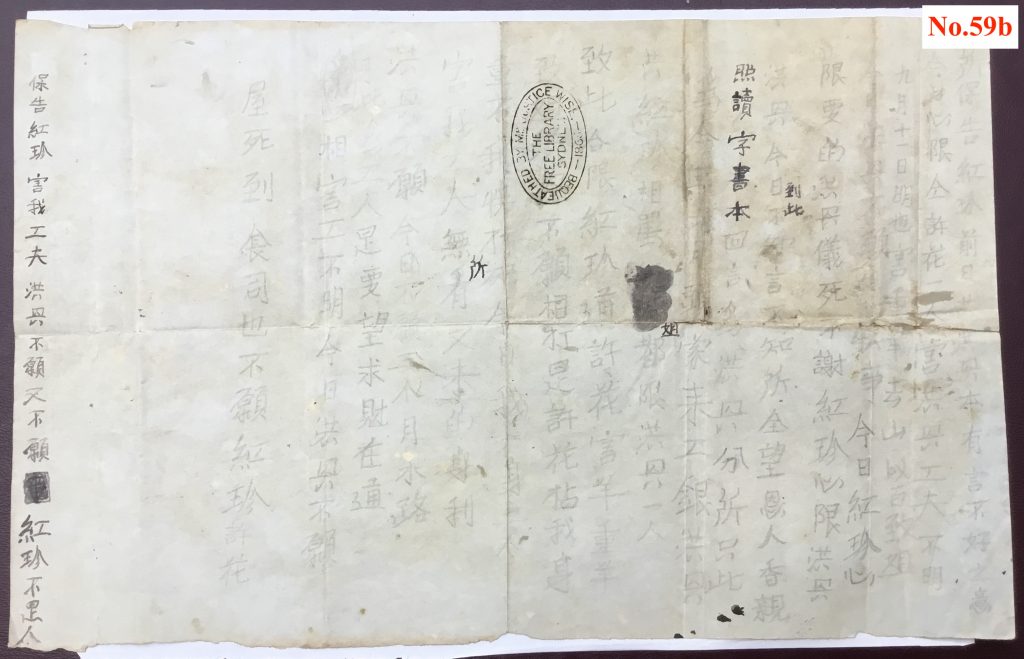

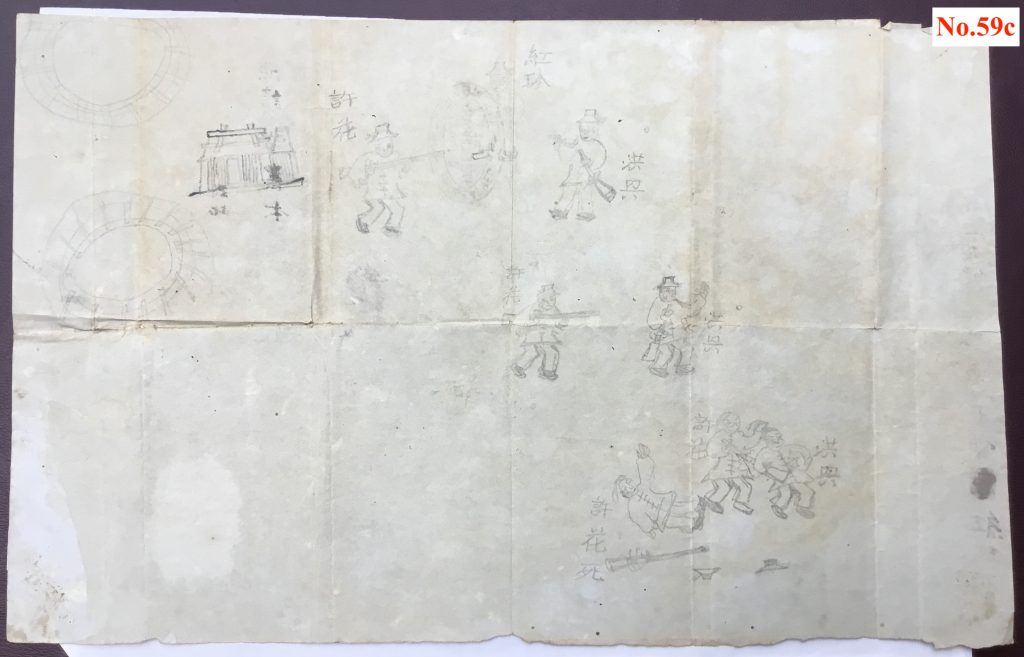

In what is likely the first piece of Chinese Australian literature (broadly defined) a man accused of murder makes his defence. (See also No. 11 & No. 22) The accused, known as Ang, was from China, brought under contract through the port of Amoy (Xiamen). He was employed as a shepherd to replace the convicts no longer available for such work. Not only did Ang not speak English but from this defence, produced in a mixture of words and drawings, it would seem his written Chinese or Fujianese was poor also. Nevertheless, his point was made clearly enough as the accompanying note in English understood it:

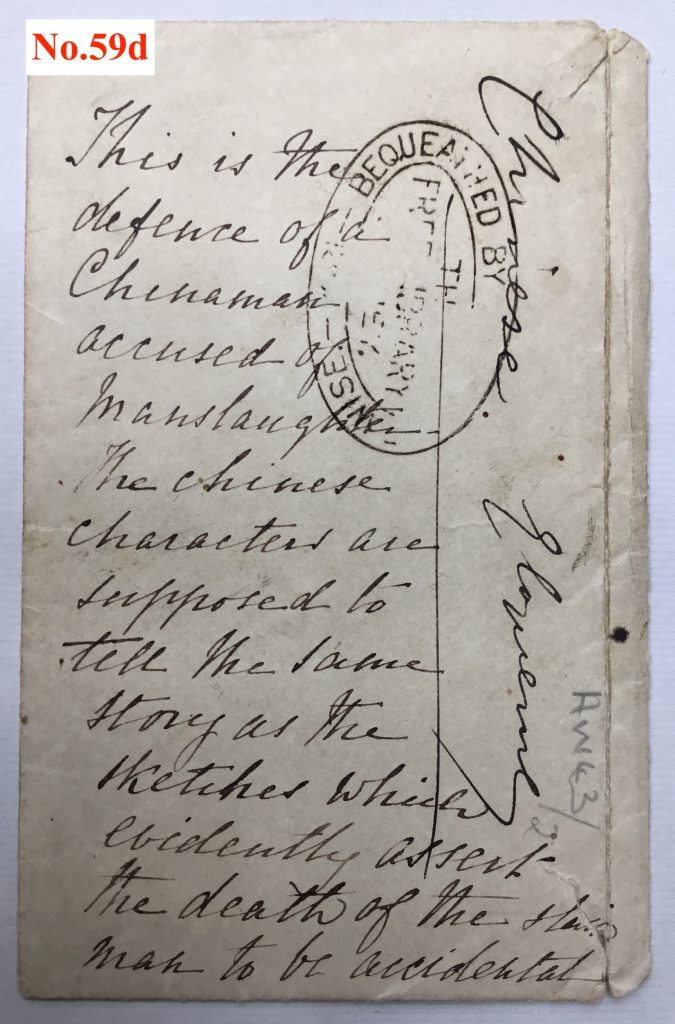

“This is the defence of a Chinaman accused of manslaughter. The Chinese characters are supposed to tell the same story as the sketches which evidently assert the death of the slain man to be accidental.”

Now in Sydney’s Mitchell Library the drawing is not in the remaining trial documents in the NSW State Archives but rather was passed by map maker Frederick Proeschal to Justice Edward Wise, a progressive politician and Supreme Court judge who did not preside over Ang’s trial (this was Justice Stephen). Edward Wise deposited the document in the then NSW Public Library.

In addition to the dramatic images and the faint pencilled text we now can link this account to an 1850 incident and trial. A report commenting that the drawing “may be found useful in eliciting the truth.” Further we now know that this same Ang was also one of the two men on Cockatoo Island researched by Shirley Fitzgerald concerning Ang’s reluctance to leave before his mate Eu’s sentence expired and their eventual pardoning in 1853. [1]

The language and the occupation of those depicted as shepherds identify the participants in this dispute and death as some of the many thousands of “Amoy” (really Fujian) people who were recruited as indentured workers into the Colony of NSW in the period after convict transportation ceased. These men are often forgotten by a history obsessed with the gold rush and the arrival of greater numbers of people from further south in China – Canton or Guangdong – and speaking other languages. Nevertheless the Amoy men frequently stayed to establish families in Australia, many of whom are only gradually discovering this ancestry.

The Amoy shepherds first began arriving in the then Colony of NSW in 1848, and while many later shifted to the goldfields many also continued to work in various locations even after their contracts expired. Our defendant was by no means the only Amoy person to appear in court, with numerous instances of cases involving poor treatment or unpaid wages under the contracts they were brought to Australia on. It was a tough life and as one report observed around this time:

“It is the intolerable cruelty that is exercised upon the Chinese labourers in this colony that causes them so very frequently to revolt and commit many outrages that might otherwise have been avoided”.[2]

When Fujianese (aka Hokkien) speakers did appear in court interpreters were frequently needed. In the case of Ang an interpreter from Sydney needed to be sent for before his trial in Brisbane could proceed. The drawing is not mentioned again in the depositions but Ang while charged with murder was convicted of manslaughter and received a sentence of five years. So perhaps his efforts to explain himself was “found useful in eliciting the truth”.

[1] Moreton Bay Courier, 26 October 1850, p.3. See also Margaret Slocomb, Among Australia’s pioneers : Chinese indentured pastoral workers on the Northern Frontier 1848 to c.1880 (Balboa press, 2014) and Shirley Fitzgerald, Red Tap Gold Scissors (State Library of NSW Press, 1996). [Thanks to Tony Anderson for pointing out the connection in the research of Margaret Solcomb.]

[2] ‘Original Correspondence’, Bathurst Free Press and Mining Journal, 12 August 1854 in Juanita Kwok, The Chinese in Bathurst: Recovering Forgotten Histories, Doctoral thesis, Charles Sturt University, Bathurst, 2018, p.71.

For more on the Amoy Shepherds see:

Responses and Reactions to the Importation of Indentured Chinese Labourers

by Maxine Darnell