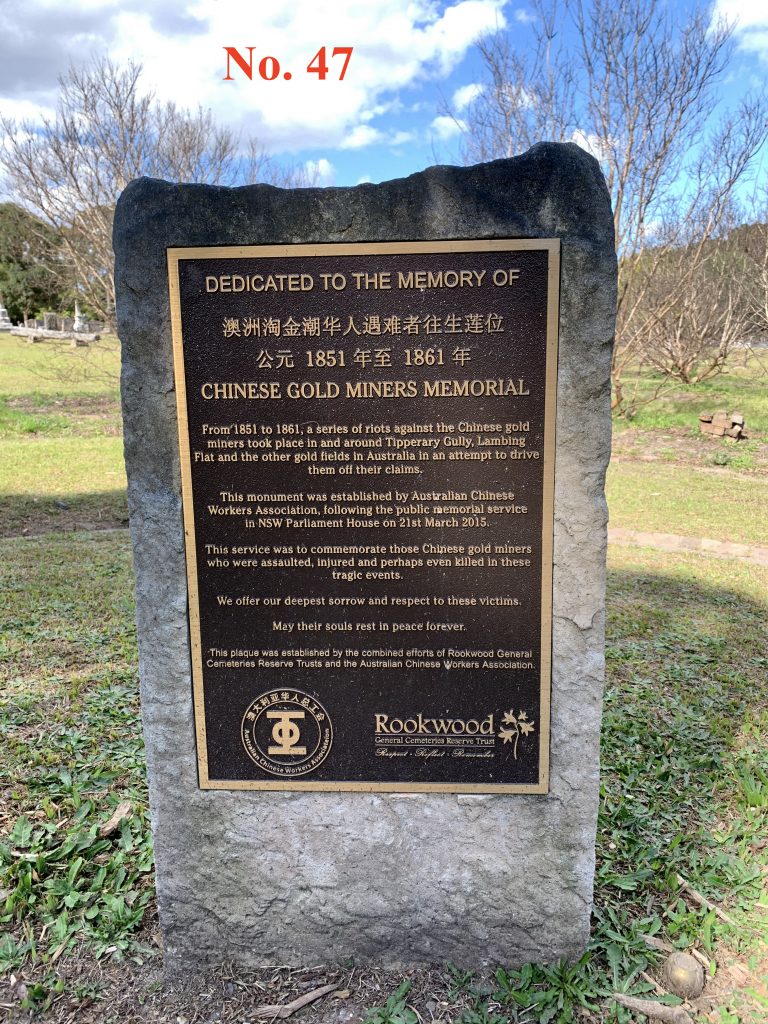

In 2015 the Australian Chinese Worker’s Association and the Rookwood Cemetery Trust erected with much fanfare – including Buddhist ritual blessings – a memorial dedicated to those who were “assaulted, injured or perhaps even killed” in a series of riots against Chinese gold miners that took place at Lambing Flat and other gold fields in Australia between 1851 and 1861. This addition to the many historical memorials dotting the Australian landscape, like all such memorials from those commemorating Captain Cook to the War Memorial in Canberra, have less to do with actual history (in the sense of what happened in the past) than with the struggles of the present. To paraphrase: “Everyone wants history on their side, but not everyone wants to be on the side of history.”

This memorial therefore, and others like it, represents a confluence of preconceptions and agendas that tells us more about contemporary perspectives and less about Chinese Australian history specifically. These perspectives (not mutually exclusive) include; recent migrant identification with an Australian past, white guilt, Chinese nationalism, anti-racism, pride in Chinese heritage, and even possibly a genuine desire to remember the past. In saying this it needs to be recognised that such a mix is typical of nearly every ‘memorial’ ever built. Memory, like history, is not easily preserved in stone, unlike contemporary prejudices.

In the case of this memorial the broad intention was to link present day Australian’s of Chinese heritage with people perceived as also “Chinese” who were undoubtedly badly treated in Australia’s past. The event was enthusiastically attended by a broad gamut of people ranging from descendants of gold miners to recent immigrants and all in between. To this extent historian’s quibbles about Cantonese or Pearl River Delta origins, the arbitrariness of dates, the fact that no one was killed at Lambing Flat (“perhaps even killed” a minor compromise on the origin assumption there were deaths), or that Rookwood Cemetery itself contains no gold miners, are irrelevant. With the addition of “white guilt”, the memorial can be said to represent a modern effort to acknowledge racism and the injustices of the past, as well as a natural desire on the part of some to identify with their nation’s past, good or bad.

There are however more serious concerns with this kind of agenda-driven memorialising. Most worrying for Chinese Australian history is it prefers to remember violence rather than the lived experience of Chinese Australians. The consequences of this are multiple and include a continued “victimising” perspective, a denial of agency, and in at least one case the destruction of an historical site in preference for this real but nevertheless narrow view. Strongly associated with this is that the focus on violence fits too easily within an historical discourse sometimes referred to as the “100 years of humiliation”. In this perspective all historical interactions of people of Chinese heritage in the world were almost all negative (not unfortunately groundless but an exaggeration nonetheless) in the period 1849 to 1949, and that it is only a strong China, and by implication a strong Chinese government, that can defend against similar injustice and racism in the present.

Some would simplistically accuse the memorial makers of one or other agenda but like history itself the story is more complicated than that. Interpretation is the key and this memorial like others popping up – while they could all do with more serious historical input – need to be seen within the social context of their times.

See More:

For an historically accurate and nuanced account of the Lambing Flat history and The Lambing Flat Riots And Its Legacies 1861-2021. Also an excellent presentation to watch: Conflict at Lambing Flat: Memory, Myth & History – a discussion with Karen Schamberger

Another of interest: The Birth of White Australia?

For an analysis of how historical sites are interpreted see:

Karen Schamberger, “Objects Mediating Identity, Belonging and Cultural Difference in Australian Museums” in Dellios, A., & Henrich, E. (Eds.) Migrant, Multicultural and Diasporic Heritage: Beyond and Between Borders, Routledge, 2020.