The skills of Chinese Australians in carpentry had made their contribution to furniture making a significant one in the urban centres of Sydney and Melbourne by the end of the 19th century. This prominence, unlike an even greater dominance in market gardening, brought Chinese Australian furniture making into direct competition with European Australian carpenters and manufactures. This was a perceived competition that led to direct racist legal restrictions in some pre-Federation colonies and later States.

The wood plane pictured is not remarkably different from that used by any carpenter, though Chinese workers apparently preferred to ‘push’ rather than ‘pull’ the plane along the wood. However it was not such technical details that led to agitation against Chinese Australian furniture makers and in some cases to discriminatory legislation. Rather they were accused of working too cheaply and thus undercutting European Australian businesses. Certainly it was true that furniture made by Chinese Australians was generally cheaper and businesses such as Anthony Horden were happy to purchase the products of the workshops (which were often nearby) and resell them to their customers.

It was a common perception of Chinese people that they worked for less and so under cut other workers but as usual the reality was more complicated. A police report in 1916 described the practical basis of this in that ‘the keeper of every cabinetmaker’s shop, produce, fruit and grocery store, employ large numbers of chinese [sic] (aliens) who are paid a weekly wage, and are provided with accommodation for their services’.[1] In ‘The Chinese Citizens in reply’ published in The Daily Telegraph, similar claims against stores made by the Anti-Chinese and Asiatic League were refuted in a table of typical expenses for a Chinese and European store in which the inclusion of ‘provisions’ made the Chinese store more expensive to operate.[2] Not that Chinese were the only workers to accept board, Thomas Smith reported paying his two European workers 18s plus board while his Chinese worker received 26s without board.[3]

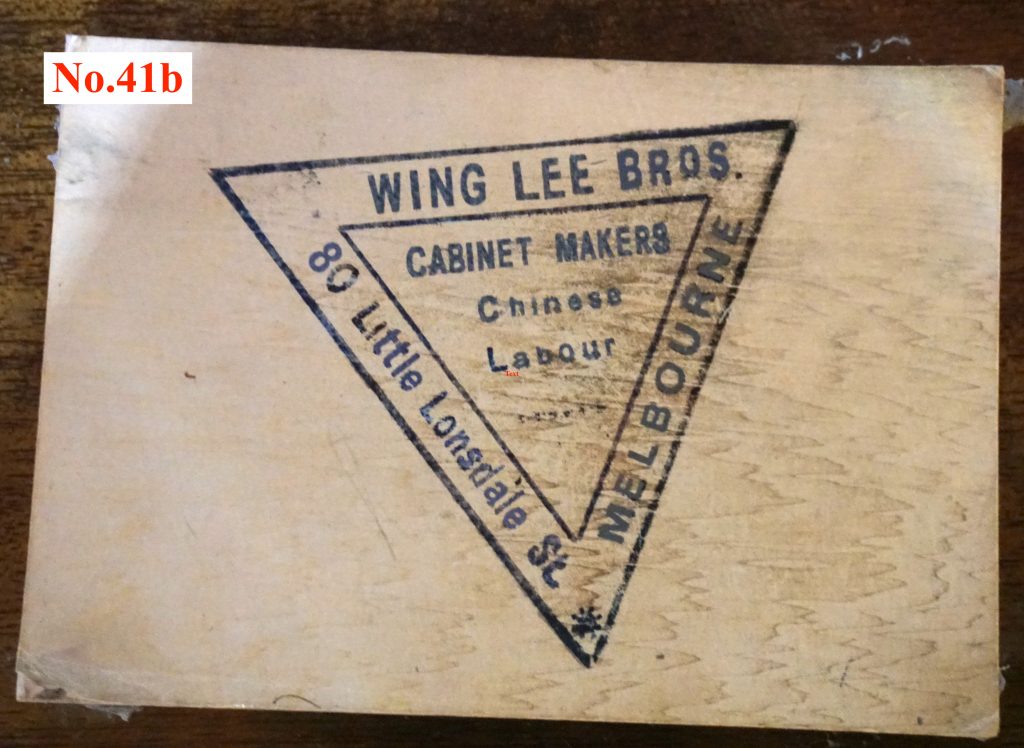

In an effort to reduce this perceived “unfair” competition, a range of restrictive measures were tried such as limiting the numbers of workers in any one workshop, banning sleeping in workshops, not allowing Chinese workers to join wages boards and most well known, because still to be seen on occasions, labelling furniture as made by ‘Chinese Labour’. This last measure was based on the hope that a customer’s anti-Chinese prejudice or perhaps pro-white enthusiasm would extend to paying more for furniture. No evidence is available to demonstrate if this was the case. While such racist legislation was passed in Victoria and WA, similar restrictions proposed in NSW were not passed on the grounds that it was discriminatory. While this was only a small victory for anti-discrimination in the prevailing prejudice, it is worth noting – then as now – that there were always those who challenged common prejudices.

These discriminatory laws are obvious, less obvious is that these mechanisms to enforce the White Australia policy often brought about the very situation that its supporters claimed to opposed. Thus Chinese Australian furniture workshops were barred from joining the Victorian Wages Boards because it was argued that owners and workers would collude in agreeing to lower wages. Yet it was in this very industry that Chinese workers proved to be most active in demanding higher wages and even launched a series of strikes. There is a paradox at the heart of the White Australia policy’s claim that Chinese Australian’s worked for cheaper wages. This is that by allowing entry of new Chinese workers on restrictive conditions (though not for furniture making) the White Australia policy ensured that these workers were more likely to be exploited. Their legally enforced employment discriminations holding many to the very low wage conditions many ‘white’ workers argued justified the White Australia policy in the first place.

See more: Peter Gibson, “Voices of Sydney’s Chinese Furniture Factory Workers, 1890–1920”, Labour History, 2017, Issue 112, pp.99-118.

[1] Australian Archives (NSW), SP11/16; Aliens Registration 1916-21, Item no. 2, No.2 Police Station, Regents St, Sydney to Department of Defence, 8 December 1916.

[2] See, ‘The Chinese Citizens in reply’, The Daily Telegraph, 22 August 1904, p.7. [https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/236886195]

[3] Report of the Royal Commission on alleged Chinese Gambling & Immorality, Sydney, 1892, p.420, lines, 15635-15639.