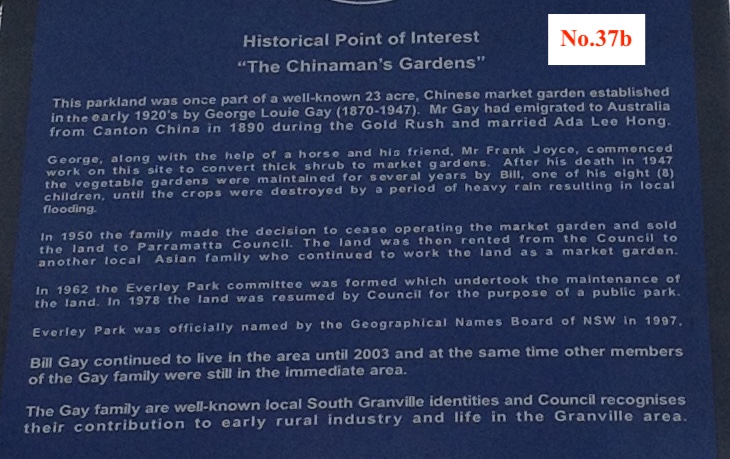

This local council erected sign is similar to thousands Australia-wide designed to point out aspects of local heritage and aid remembrance of things past. It is also typical in being slightly erroneous (there was no 1890 gold rush) and perhaps less typical but not unique in perpetuating a patronising and racist designation. While such a marking of history and heritage is undoubtedly important it is also important to remember context and to be aware of the many political factors that go into such marking.

That most people are aware of Chinese people in Australia’s history as either gold miners or market gardeners – as opposed to business tycoons, newspaper editors, doctors or opera performers – is a product of the White Australia policy on both a physical and psychological level. Physically the White Australia policy was highly though not absolutely successful in so far as it limited numbers of arrivals. It also limited the range of job opportunities people of Chinese origin had, so that market gardening for a variety of reasons (see No. 21 and No. 32) became a significant source of income. Though it is worth nothing that at any one time only 30% of Chinese people in the early 20thcentury were actually market gardeners – a high proportion but by no means every one or even most.

This brings us to the psychological impact of the White Australia policy, which was designed to “make Australia white”, and in terms of Australian’s perceptions of themselves was extremely successful. So much so that Billy Gay, the Australian-born son of George Gay the market gardener remembered here, would habitually refer to “Australians”, meaning Australians of European descent and not include himself in this designation. For the Australian population of European, particularly British heritage, this meant that history and heritage for many generations did not and could not include people of Chinese origin. Where their presence could not be completely whitewashed people of Chinese origin were restricted to nameless categories of goldminers and market gardeners. Hence the typical designation “The Chinaman’s Garden’s” perpetuated in this signage despite the name of the man who established it, George Louie Gay, and his son Billy Gay who worked on it for many years and attended the local school, being well known.

Nevertheless this marking of history and heritage is to be commended and is to be encouraged. But such marking of history is not always as simple as it seems. George Gay was a father and husband, also managed banana plantations in Fiji for the Wing On company (see No. 39), sent his son to the home village in China to ensure he learned Chinese, and ran a market garden where Rose Bay Golf Course now is. (It is to be hoped a similar sign has been erected there.) The recognition of Australia’s Chinese past is growing but the motivation for this can range from a simple wish to acknowledge all in a multicultural society, to a desire to attract more tourists (see No. 38), and even from a craving to establish links to a pioneering past. All commendable aims in themselves but aims that sometimes leave history itself a poor second.