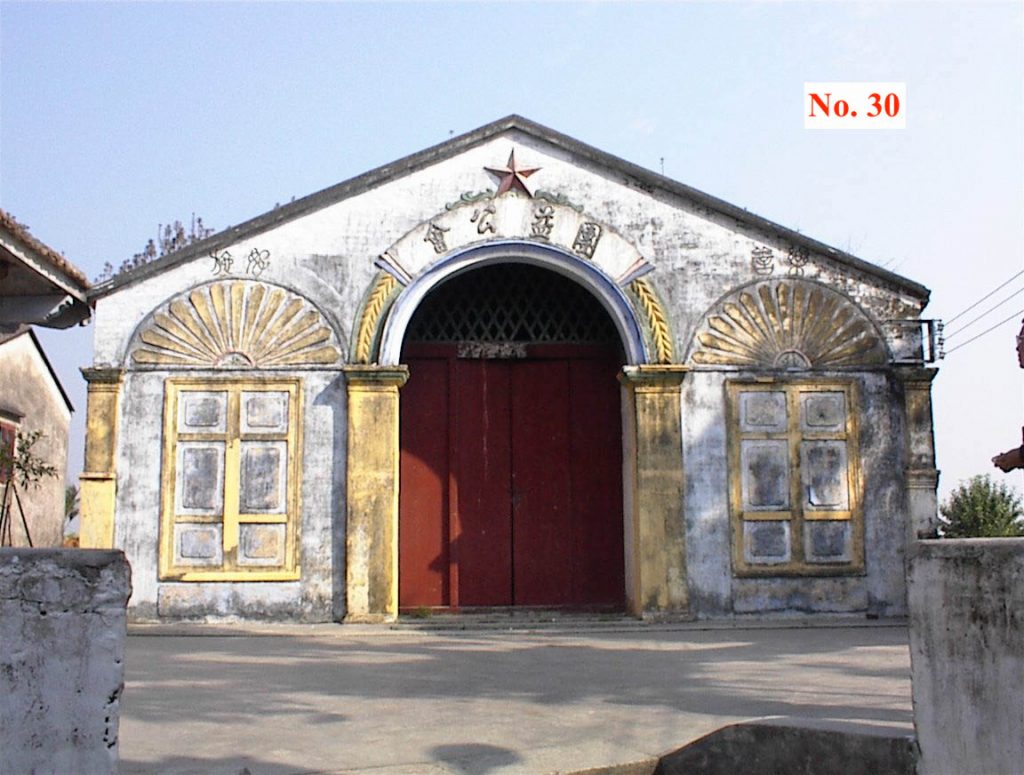

In the south China village of Chung Kok – 象角 – (or Xiangjiao in Mandarin), is a small community hall built in 1913. The purpose in erecting this community structure at that time was to make a place to dispense medicines to the people of the village. However, since 1913 the hall has served many purposes, with its contemporary one being an exhibition space for historical displays on the village and its region. This contemporary interest in Chung Kok history focuses on how far into China’s past that history goes. Nevertheless, the building itself is evidence that this history also extends far beyond the Pearl River Delta or nearby Hong Kong or even the provincial capital Guangdong. For in 1913, when the leaders of the village of Chung Kok proposed a hall to improve the health of their some 11,000 residents, they were able to draw upon the resources of many Chung Kok members living and earning in places as far away as Port Darwin and Atherton in northern Australia, Sydney and Melbourne, as well as Hawaii and San Francisco across the Pacific Ocean.

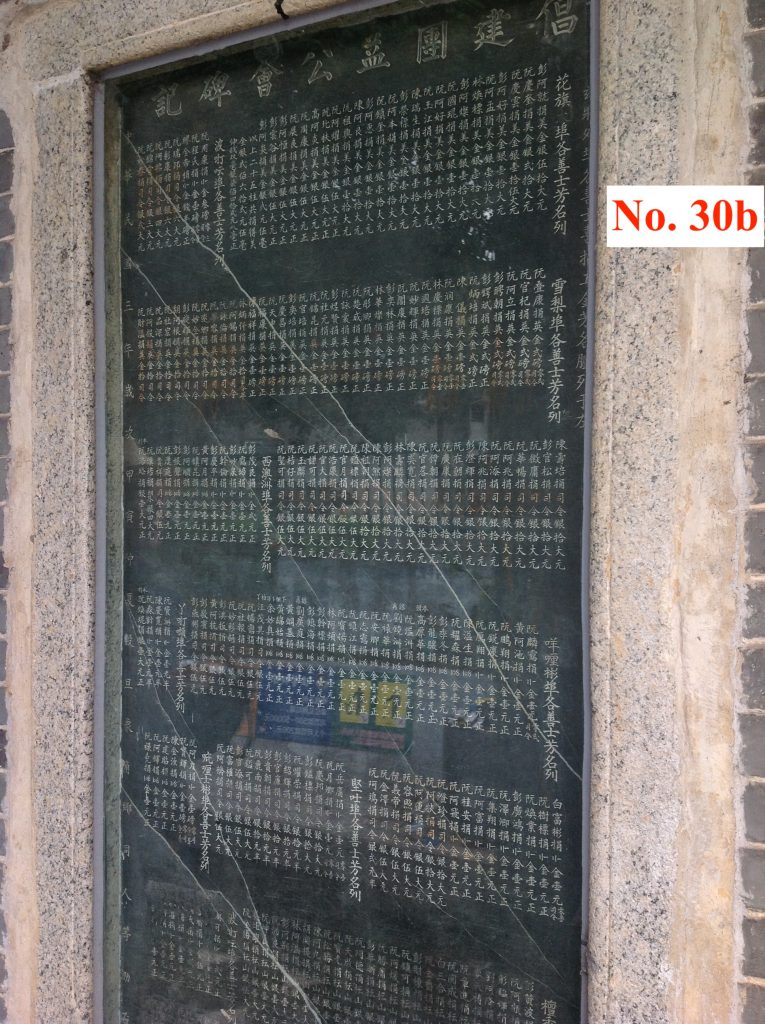

All this is known because on its erection in 1913 the right side of the Chung Kok community hall had two large slabs of black slate embedded into its side wall. The first slate is carved with a list of 222 donors listed by name and grouped according to where they were living as well as the amount of their donation in the currency of that place. Thus, in the order inscribed, the donors of 1913 were living in: San Francisco (lit., First Port of the Land of the Flowery Flag) – 25, Port Darwin – 24, Sydney – 63, West Australia – 13, Melbourne – 32, Atherton – 20, Cairns – 13, Brisbane – 6, and Hawaii (lit., Sandalwood Mountains) – 26.

How was the Pearl River Delta village of Chung Kok able in the second year of the new Republic of China to draw on resources from around the Pacific to assist in improving the health of its members? The answer goes back to the establishment of Hong Kong in the 1840s that gave these and residents of nearby villages access to European shipping and initially the Californian and Victorian gold rushes of the 1850s. [See No. 20] Subsequent generations not only continued to travel overseas to earn, but built up a sophisticated remittance system to ensure money flowed back to their families. [See No. 14 & No. 29]

This was a system villages such as Chung Kok were able to access to help provide community benefits, not only vaccinations but also schools, reading rooms and equal education for women. This latter is demonstrated in the neighbouring village of Long Tou Wan by Chang She May, whose grandfather practiced traditional Chinese medicine in Sydney. On her return from Shanghai where she studied western medicine Chang She May used a similar community facility to provide medical support to her fellow villagers. (Interview, July 2000)