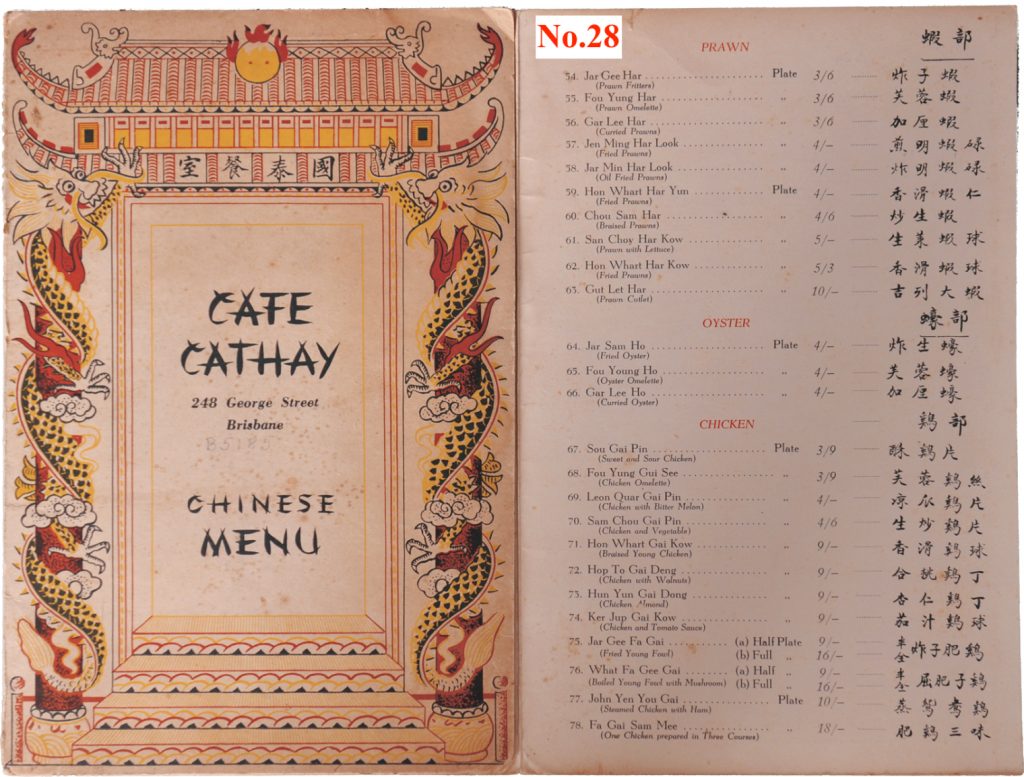

This seemingly ordinary Chinese restaurant menu from the Cafe Cathay Brisbane is evocative of a number of notable features of Chinese Australian history, not least the enforcement by the White Australia policy of a form of bonded employment under the “Chinese occupations” category. For many, the Chinese cafe is symbolic of Chinese Australian history and that this has been recognised widely can be seen by the inclusion of this specific menu in the overseas Chinese collection of the Zhongshan History Museum collection (see No.7).

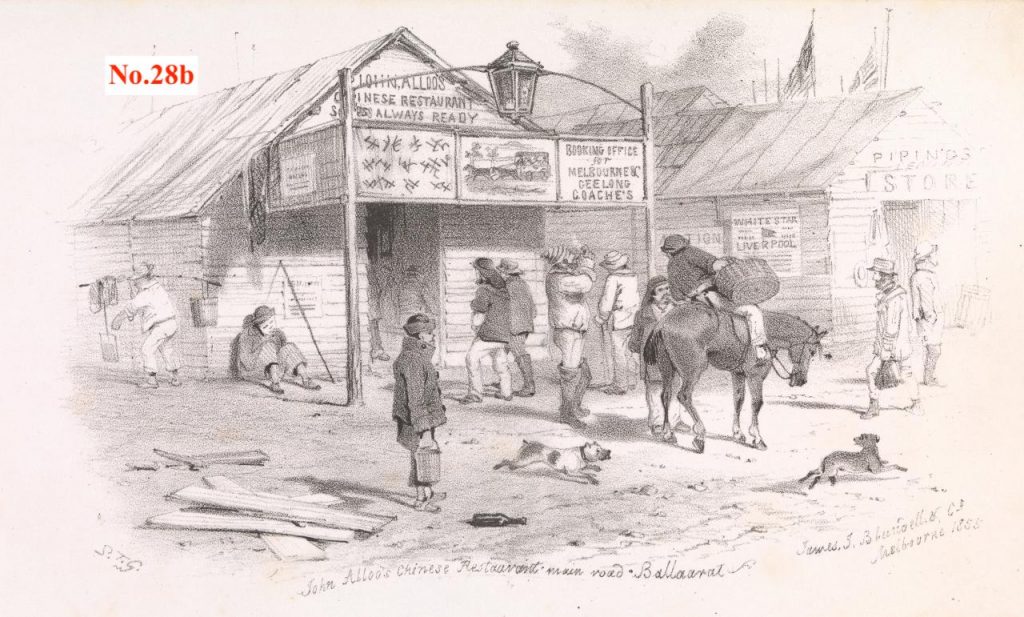

Investigation of the role of the Chinese cafe and its adjunct the “Chinese Australian meal” reveals more than the standard tendency of ethnic communities to set up restaurants serving food from “home”. Nevertheless the origin of Chinese cuisine in Australia can be traced to just this tendency on the Victorian and NSW goldfields where many “chop shops” were set up serving gold miners of all backgrounds.

By the end of the 19thcentury both cheaper “chop suey” places and up market cafes and restaurants such as Sydney’s Quong Tart Tea House in the Queen Victoria Building and a the Pekin Cafe of Melbourne with its Sydney branch (see No.11) were plentiful. However the Dictation Test introduced in 1901 (see No.1) gradually reduced the size of the Chinese community in Australia as people retired back to their home villages and relatively few were allowed to replace them. This was a fall in numbers minimized at first in Sydney and Melbourne as people from the rural districts moved into the urban centres. But as numbers nevertheless slowly declined a consequence was to reduce the available workforce for Chinese employers in market gardening, furniture making and cafes.

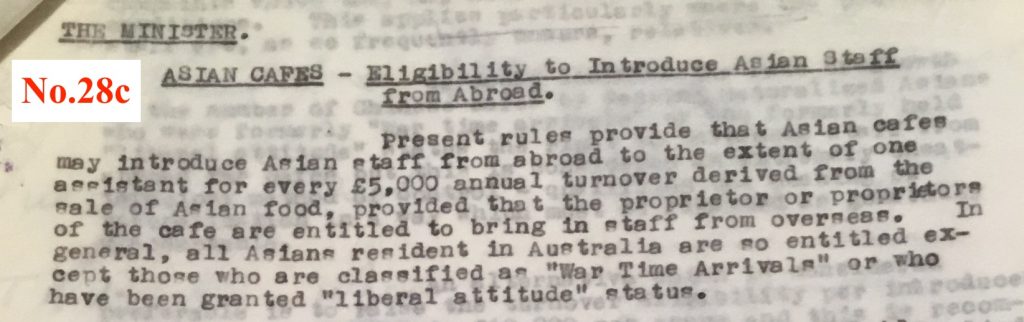

With both demand and supply (in the villages) high two mechanisms swung into operation – smuggling and manipulation of the Dictation Test exemptions (see No.77), in which the White Australia policy bureaucracy became partiality complicit. Smuggling and bringing people under Certificates of Exemption to the Dictation Test as either students or substitutes or under the category of Chinese occupation created a situation that allowed market gardens and some cafes (but not furniture makers) to continue. The irony here is that it was the very mechanisms of the White Australia policy – partly set up to protect white workers from supposed cheap Chinese competition – that created and maintained for many years forms of bonded and low wage work within these market gardens (see No.32) and cafes.

As far as Chinese cafes were concerned this situation expanded in the post 1949 period as Hong Kong filled with refugees from the new China, most Cantonese speakers and many with Australian connections. While the Australian government refused British pleas to take people from Hong Kong as refugees it did continue to allow many to enter Australia as cafe workers provided the cafes served a proportion of “Chinese meals”. The result was the establishment in nearly every rural town of a cafe or restaurant serving “Chinese Australian meals”.