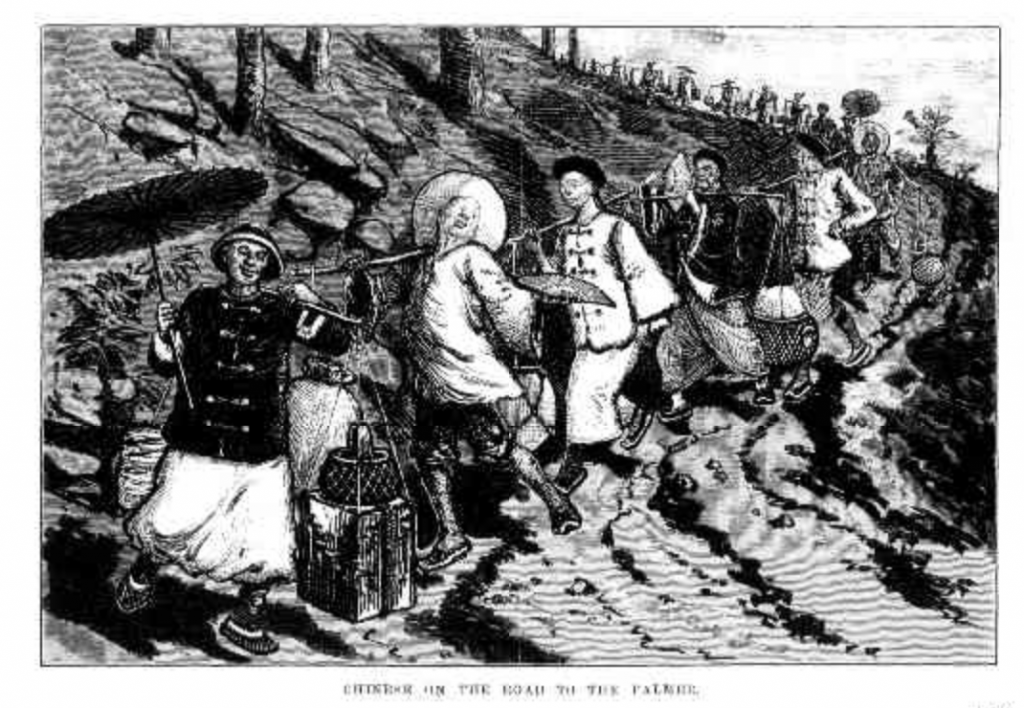

As the various Australian colonies developed their anti-Chinese immigration attitudes and then laws, their British imperial overseers took a keen interest. In general, the imperial attitude was that such restrictions were a bad idea. Cheap labour was best, and why offend governments such as the Chinese or Japanese? As part of this oversight the British Foreign Office sent out one of its people – James Dundas Crawford – who had some knowledge of the Chinese and even spoke Mandarin. Dundas Crawford was sent at a time when the Colony of Queensland was concerned as thousands of Chinese goldseekers were arriving at Cooktown and walking inland to the Palmer River goldfields. This was in 1877 and the report of his observations of Chinese activity in Queensland, NSW and Victoria was duly sent to the Foreign Office.

The report makes fascinating reading. It is not only a rare example of a wide-ranging investigation with many interesting comments but even rarer, it is written in a, for the times, objective and sensible manner. Despite this the Crawford report remains an underutilised resource. Historians have done what they all too often do with interesting material, plunder it for a quote or statistic relevant to their specific task and then leave the remains to languish in a footnote. It was in a footnote I found the Crawford report many years ago and intrigued I tracked it down in the copy of the voluminous British Foreign Office files kept in the National Library of Australia.

After reading it I did two things that I am repeating here. The first is to make the full report – it is only 33 pages long – available for people to read in its full Victorian glory (long sentences and patronising tone mostly). Secondly, I wrote an article that basically described the Crawford report and provided some context in the hope of encouraging its wider use as a source. While its wider use has certainly occurred, this aspect could perhaps be improved still.

Why do I like the Crawford report so much? Mainly because in a period when there is virtually no Chinese voice to be found, Crawford’s outsider view (outside the white colonial concerns of the colonies) provides us with the next best thing. At one point he spoke before a crowd of European miners in Victoria on behalf of Chinese miners ‘urging their claims to be allowed to mine on the rush’.[1] Yet while Crawford was by no means a modern multiculturalist, he does give us an analysis that is closer to the Chinese perspective than nearly anything else we get until the beginning of the Chinese language press in Australia some twenty years later. Furthermore, I think people should read sources directly rather than be reliant on the interpretation of academics – something modern technology now makes so much easier. Enjoy!

The Crawford Report, Shanghae 1877

- Great Britain, Foreign Office Confidential Prints: No.3742, Notes by Mr. Crawford on Chinese Immigration in the Australian Colonies, J. Dundas Crawford, 1 September 1877.

My write up on the Crawford Report

- Michael Williams, ‘Observations of a China Consul’, Locality, Vol. 11, no.2, 2000, pp. 24-31.

Corrections – a few years after I wrote my piece on the Crawford report a publication utilising many of Dundas Crawford’s letters to his family allows some clarifications. This was: Bob O’Brien, What Ho, Crawford, Old Chap: an Anglo-Scot Interpreter (1850-1903), Dorset Enterprises, Wellington, 2004.

- I discussed why the British sent Crawford. However, in a letter home he claims it was his idea. Certainly, he was disappointed the report did not lead to anything.

- I speculated about whether or not Crawford spoke Cantonese but in a letter to his sister he makes clear he spoke only Mandarin but that he was able to use this in Australia nevertheless as well as English.

Who was James Dundas Crawford?

His seems in many ways a sad story. His mother died when he was two, then he was shipped off to distant relatives before Eton at 7 years of age. His father went to New Zealand as a magistrate while he joined the British Consular Service. Not long after returning to Shanghai and submitting his report Dundas Crawford suffered a mental breakdown and spent the rest of his life living quietly in England before dying aged 52 in 1903.

See also Noreen Kirkman, Chinese Miners on the Palmer (Presented to a meeting of the Society 28 August 1986).