What the “Indian Community, resident in Victoria”, thought [1]

In 1901, a group of “British Indian subjects” living in Fitzroy, Melbourne at the time the Immigration Restriction Act was being debated in the Federal Parliament then located in Melbourne, wrote to the Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain, MP. This letter perfectly comprehends the debate held between the Colonial Secretary and the Australian colonial premiers only a few years previously and underlines the compromises and hypocrisy that was the outcome of this meeting. Claiming to represent “the Indian Community, resident in Victoria” the writers requested the Colonial Secretary, Joseph Chamberlain to “lend your assistance in a matter which is of vital importance to our welfare.” The matter of vital importance was of course the possibility that the new immigration restrictions would restrict people such as themselves from coming to Australia.

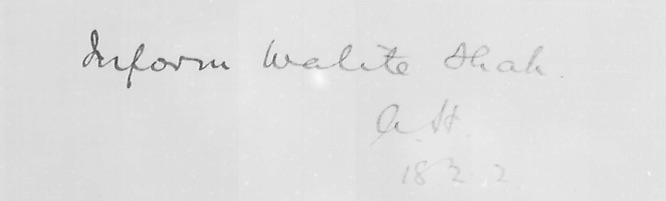

The writers, Walite Shah and ten others went right to the heart of the matter by asking:

What is the difference between an Indian and any other member of the British nation?

They followed this up by outlining a history of membership and loyalty to the British that would have been well known to the recipient. Chamberlain would have been “well aware” that Indians had been “members of the nation and under British rule” for “the whole of the past century”. Perhaps laying it on a bit thick, Walite Shah and his associates added that they were “proud to be under the wise and merciful rule” of the British because they knew that “there is no other in the world which is so good”.

Having staked their claim, the representatives of the Indian residents of Victoria then asked why “our own government” would “wish to separate us from herself” and put “us as strangers with the outside nations of the world”. For these proud members of the British nation it was “very painful” to be “put along with the Chinese” who they felt (writing just after the events of the Boxer Rebellion), were a “defeated and dying race”. The writers claimed that before the introduction of this proposed immigration restriction, we considered “ourselves”, and “especially those who do the bulk of the fighting of the Empire”, as “all people under British rule” and as “part of the British nation”. The writers now pleading that it seems “we are separated by the will of the British Government” from “the nation” while the actions of the “Commonwealth Government” are “putting us amongst the outside peoples of the world”.

At this point Walite Shah and his fellows asked:

Who has the right to call Indian people “outsiders”?

The letter emphasises again that Indians are “valuable subjects of the British Government”, as proven by the desire of Russia to “put her teeth on India” and its inability to do so because the Indian people are “obedient and faithful”, as well as the willingness of many Indian subjects to “give their blood” and “if necessary, to die for the Empire, including against the Chinese. The recent preparedness of “Indian subjects of the King, in Victoria” to volunteer for service in the Boer War after the defeat of the Battle of Colenso is specifically cited as an example of the inclusiveness within the “British nation” the writers wish to prove.

Given the willingness of Indian subjects to serve the British, the writers state they are “greatly pained” by “so much talk of a white Australia”. Having “dark-coloured skin” is not a reason for being “cast off and put along side Chinese and Japanese” while outside nations such as “Germans, Russians, French, Italians” are not mentioned. Once more a pointed question is asked:

Do the Members of Parliament consider the justice of this side of the question?

The willingness of the Indian people to fight for what are the quarrels of “the British Government with someone else” are again asserted and seen as part of a bargain where it was “always understood that we were members of and helping the British Nation”. The remorselessly logical questions continue:

If we are members of the British nation, then why should we be denied equal rights with any other members of the same? Other members of the British nation can go wherever they like and do whatever they please within the limits of the British dominion; so should this right be denied us? Is it just that the bargain be all one-sided?

This appeal to the Colonial Secretary ends with an all too sharp analogy of a family where one brother it appears “is not so handsome as the others” but in every way endeavours to “please his father” only to find his brothers “through some motive which has the appearance of family jealousy” do not “like him to come into their homes” while they “keep the right to go and do whatever they like in his house”.

The letter ends stating that the writers are “anxious to know how it is that we who are members of the British nation are denied equal rights” and with masterly understatement:

We do not think this is fair, although the Government seem to.

The only reply we have apparently to this appeal on behalf of the equality of subjects of the British Empire is a letter appended to the copy sent onto the Australian Governor-General and passed by him to the Australian Prime Minister.[2] The Colonial Secretary had himself argued, abet weakly, the cause of British Indian subjects at the Imperial Conference of 1897, and had urged the Australian colonies to adopt the Educational Test now incorporated into the just passed Immigration Restriction Act. None of this prevented Chamberlain, with an astonishing lack of shame only a member of the British ruling class it seems could manage, from asserting that the legislation:

… does not appear to cast any reflection upon any class of His Majesty’s subjects.

For Chamberlain the well put and sincere questions contained in the appeal, similar to, yet more strongly asserted than his own, were apparently so indisputable, that these arguments of His Majesty’s “Indian residents in Victoria” could only be dismissed by ignoring them in the grand fashion of imperial hypocrisy.

[1]NAA: A8, 1902/182/1, Walite Shah, et al., to Joseph Chamberlain, 25 October 1901.

[2]NAA: A8, 1902/182/1, Joseph Chamberlain to Lord Hopetoun, 24 December 1901.