Histories of the White Australia policy in general and of the Chinese in Australia specifically are replete with references to the “Dictation Test” and its corollaries the Certificate Exempting the Dictation Test and Certificate of Exemption. (See No. 1 & No. 77). However few go into detail as to what these tests actually were and how they were given in practice. In fact the essential “gross chicanery” of the Dictation Test as it existed for over 50 years is so unique as a legal instrument that very often its fake nature is misinterpreted as a merely hard or unfairly given test.[1] The reality is far more shameful as was recognised by too few both in the 1st Australian Parliament that passed it in 1901 or the 22nd of 1958 that finally authorised its abolition.

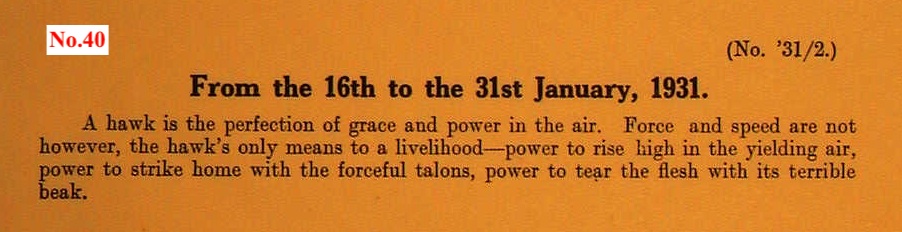

The key to the operation of the Dictation Test as an instrument of immigration was that it was to be given at the discretion of a Customs (after 1945 Immigration) official in any European language. Failure to pass the test was a crime and consequently the person who failed to write down the 50-word passage as dictated to them became a “prohibited immigrant” liable to a term in goal and deportation.[2]

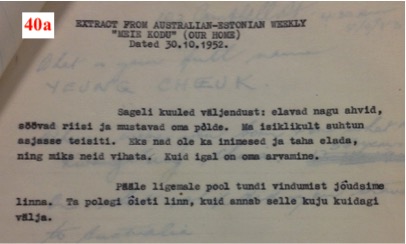

Those selected to be given one of these 50-word tests were of course overwhelmingly people of Chinese or other “non-white” backgrounds. Though it was not unknown in the course of its history for people of “white” or even British background to be given it on occasion.[3] On occasions the giving of a Dictation Test to a European creating a public outcry that never accompanied the testing of non-whites. But of course the test passage shown here, while in convoluted English, is nevertheless not an impossible passage to write if dictated to someone with a reasonable command of the English language. Hence the “chicanery” well spotted by McGregor, for the “any European language” of the legislation did not mean a Frenchman was given a test in French but rather that should the person selected seem able pass one test given in English then a test in another language could be chosen. That in Estonian was given to Yeung Cheuk in 1956 for example.

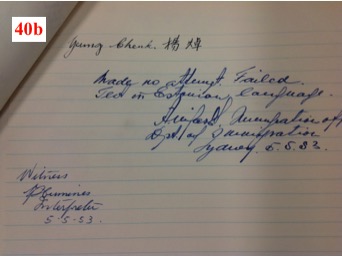

Thus a real Dictation Test is in fact a blank sheet of paper similar to that left after Yeung Cheuk had, in the words of the Immigration officer, “made no attempt” to write in the Estonian of the test given to him. Yeung Cheuk (see ‘A deserter’s fate’) had entered Sydney and worked for a year as a Chinatown cook before his enforced return to Hong Kong after a brief stay in Botany Bay Gaol. His Dictation Test was nearly the last before its abolition in 1958, a move which the Labor Party’s Jim Cairns recognised “should not obscure the fact that there is still a restriction based purely on colour.”[4] It would be many more years before the White Australia policy itself would go the way of the gross chicanery of the Dictation Test.

[1] As Senator McGregor put it: “The Government had placed itself on the horns of a dilemma, as, if the Bill were honestly administered, it would be inept, and, if not honestly administered, it would involve Parliament and its officers in a piece of gross chicanery.” The West Australian, 14 November 1901, p.3. Australia chose the chicanery.

[2] The Act required a dictated passage of not less that 50 words. This had been changed from the original ‘fifty words’ which had generated a court defeat when it was found that the exact number of 50 words had not been dictated.

[3] The most famous such case being that of Egon Kisch given the test in Scots Gallic only to have this struck down by the High Court as too obscure a language to serve as a European language, much to the disgust of Scots. The Kisch case is remembered for being an anti-Fascist European persecuted by then Attorney-General Robert Menzies. That is, for its white mainstream political links while the similar persecution of thousands of non-whites by the same test goes largely unremembered.

[4] Hansard, House of Representatives, 22nd Parliament, 3rd Session, 1 May 1958, p.1422.

Translation from the Estonian: ’You often hear people say: they live like monkeys, they eat rice, they spread human waste on fields. I have a different opinion. They are people, too, and want to live. Why hate them? But each to his own.

We made little progress for almost half an hour but eventually made it to town. It’s not really a town, but comes close.’

(Thanks to Richard Horsburgh for obtaining this translation)